Even rocks don't live forever: contact with air, water and molecules dissolved inside of them cause them to decompose over time. This process is known as weathering.

Rocks such as the Alps or the pebbles by the sea are silicates. This group of rocks is most common on Earth. Silicates bind the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide during their weathering. The warmer it is, the faster this happens. Climate change therefore accelerates this process and, in the long term, ensures that it becomes cooler again. Put simply, silicate weathering thus acts as a natural thermostat, counteracting global warming more and more as the temperature rises.

If this process could be accelerated, it might also be possible to slow down man-made climate change. "To do this, however, it is necessary to better understand the weathering that takes place naturally," says Prof. Dr. Christian März of the Institute of Geosciences at the University of Bonn. "This decomposition occurs not only on land, but especially in the ocean - both directly at the bottom and several meters below the seafloor. However, how strongly and how quickly it takes place, and what it depends on, has only been insufficiently researched."

"Compost heap" at the bottom of the sea

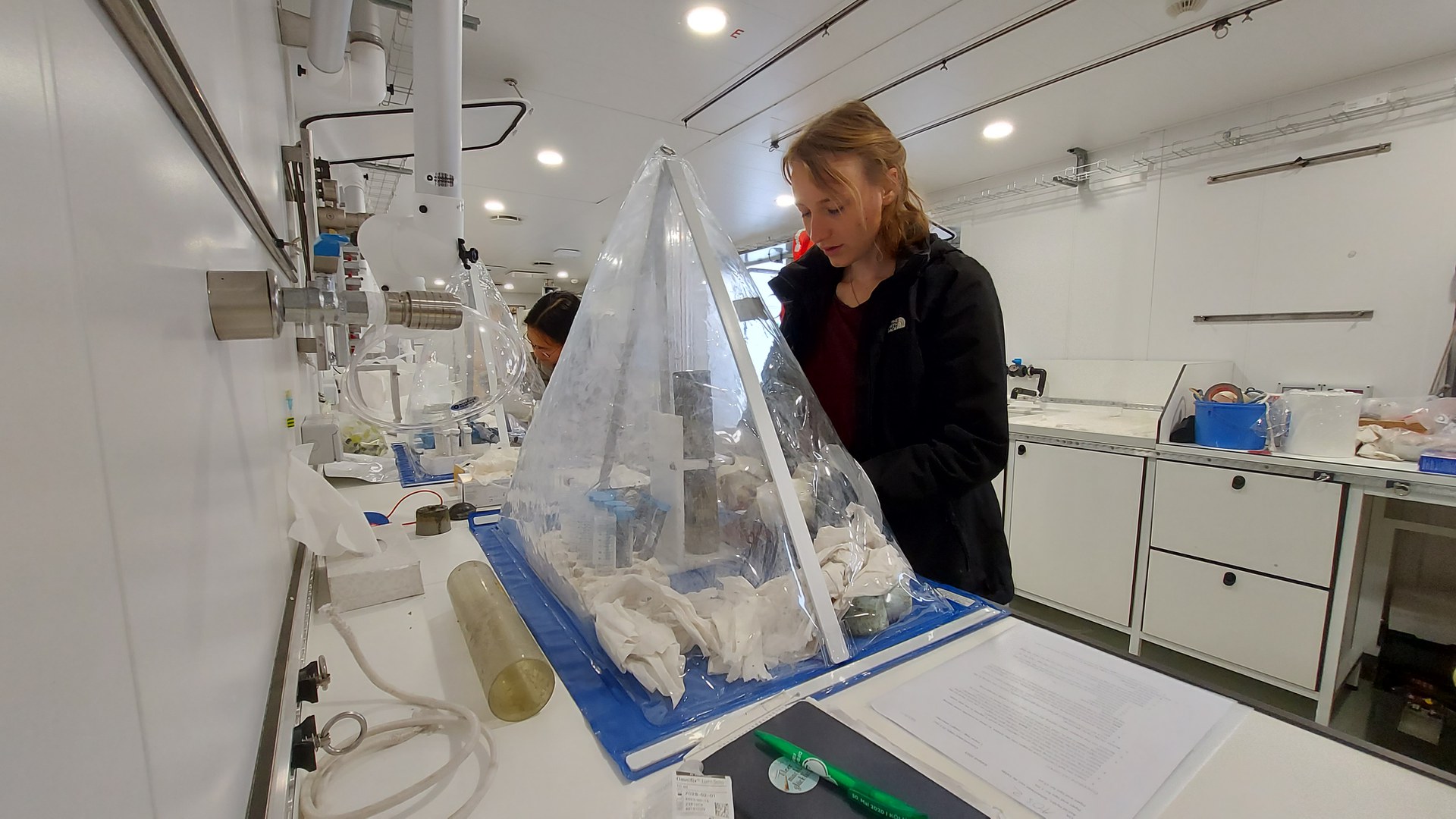

Together with his doctoral student Katrin Wagner, März has been aboard the RV Belgica in recent weeks. The two are studying how the mud-like deposits on the seafloor change over time. To do this, they are punching sediment cores out of the bottom - on the one hand in the Hvalfjördur fjord in southwest Iceland, and on the other in the offshore shelf area in the southeast of the island.

"Put simply, the bottom of a fjord resembles a compost heap," explains Katrin Wagner: "A lot of organic material collects there. Some of it comes from dead algae, and some is washed into the sea by rivers from the surrounding land. At the same time, silicate-containing soil also enters the sea with it."

At the bottom of the sea, the organic material is decomposed by microorganisms. This creates chemical conditions that presumably also promote weathering of the silicates. March and Wagner are comparing how these processes differ in the Hvalfjördur fjord and on the shelf, where there is much less organic material and the bottom consists of much coarser sands and small stones.

The results of these analyses could also provide clues as to whether and to what extent silicate weathering is suitable as a tool against global warming. "Even if that works out, however, it's only a small component in the fight against climate change," März emphasizes. "The most important thing is still to significantly reduce the amount of emissions."

No time for boredom

The RV Belgica has just returned to port in the Icelandic capital of Reykjavik. Before that, the researchers and crew spent nearly three weeks continuously at sea. For the first few days, März was plagued by seasickness. "Even after quite a few ship expeditions over the past 20 years, my body always needs a few days to get used to life on the water," he says.

For him, it's now back to Bonn. Katrin Wagner, on the other hand, will stay on board for the next part of the voyage to southern Greenland - another almost five weeks. Nevertheless, there is no such thing as boredom on an expedition of this kind, not least because free time is in short supply. "There is always a lot to do," says März. "When you do get some rest, you enjoy the view, keep an eye out for whales or birds, and have a cup of tea."

Project information:

The DEHEAT project is funded by the Belgian Science Policy Office (BELSPO) and runs until 2026. A website with detailed background information can be found here: https://coastalesw.wordpress.com1

More information about the expedition of the RV Belgica, the stations of the voyage and photos can be found on the following website: https://uploads.knightlab.com/storymapjs/815d327687abd8892b03dbde7cf373ce/deheat-1/draft.html2

Contact for the media:

Prof. Dr. Christian März

Institute of Geosciences, University of Bonn

Email: cmaerz@uni-bonn.de