Kids and teens often complain about school, but interacting with others during the schoolday fulfills a need for contact with their peers, which is important for their well-being and social development. Children suffering from chronic illness are often forced to go without such contact. Conducted in collaboration with the University of Bonn Humanoid Robots Lab, the project is titled “Privacy-Friendly Mobile Avatar for Sick Schoolchildren” (PRIVATAR). The idea is to help sick children by enabling them to participate in lessons and everyday school life through the agency of mobile robots. At the school, the robots are used as avatars, functioning as the legs, eyes, ears and mouth, as it were, for home-bound sick children. One big challenge to be overcome is protecting the privacy of classmates, teachers and of the sick children themselves.

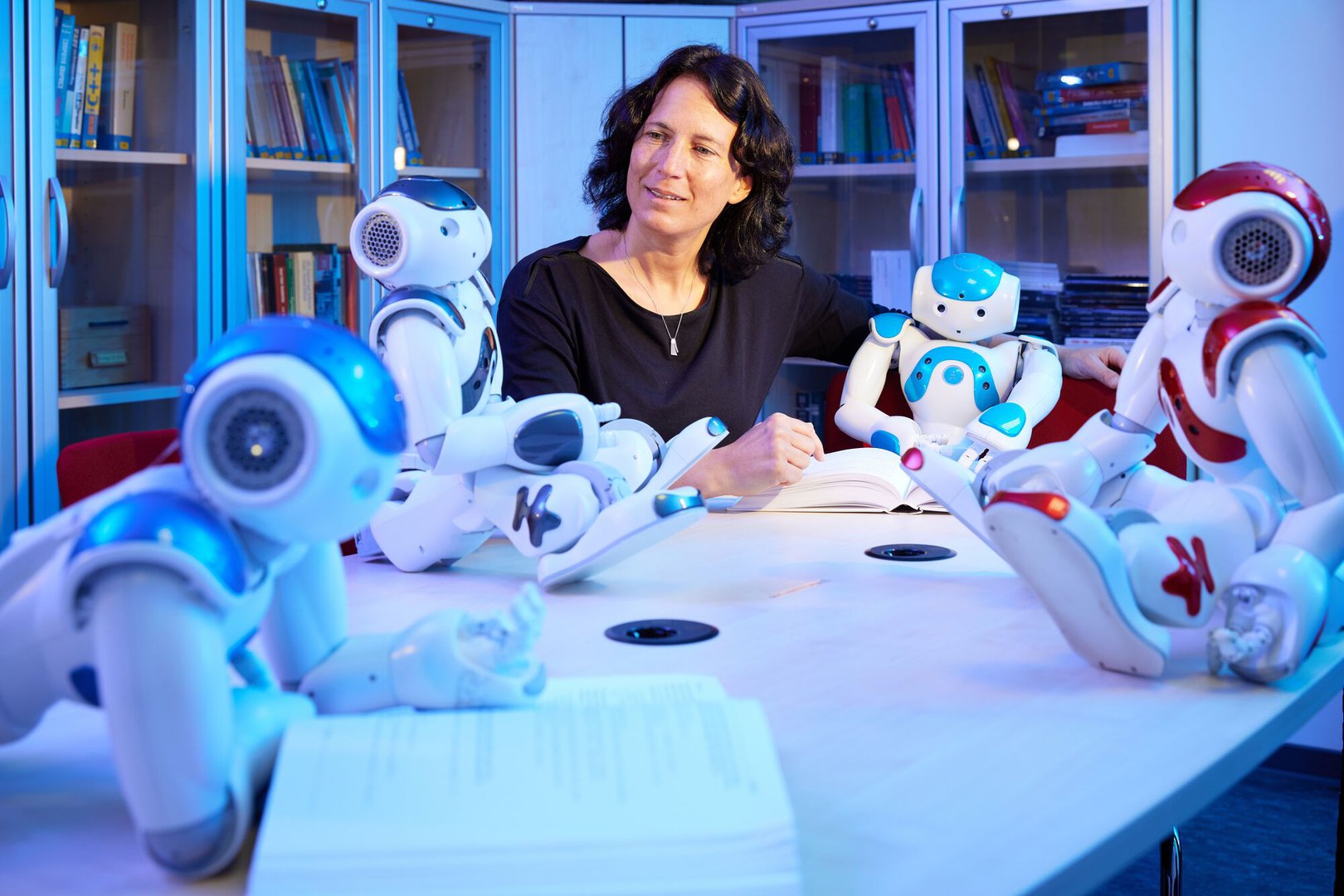

“The robots have many different sensors that enable them to safely navigate their environment and interact with people,” explains Professor Maren Bennewitz, Head of the Humanoid Robots Lab, “detecting furniture, for example, but also perceiving movements and recognizing faces—to which or whom the robot can then react. Much of the data processed to make this possible concerns the private sphere of the individual, such as location, movement patterns and video-recorded data.

Professor Bennewitz is a board member of the PhenoRob Cluster of Excellence and a member of the Modelling Transdisciplinary Research Area at the University of Bonn. She elaborates: “Our goal is to develop mobile robots that use as little sensor data as possible, so as to protect the privacy of individuals in the classroom while ensuring safe and efficient interactions.”

Bennewitz and her team are deploying their expertise in a sub-project devoted to making robot navigation user-friendly for children and teachers, which includes in particular the ability to enable and disable sensors based on user preferences. Nils Dengler, a doctoral student involved in the project, explains: “Among other objectives, we want to have controls allowing children and teachers to configure their desired settings without needing assistance. For example, users can change privacy settings and choose how closely the robot may approach them.”

One special challenge in this regard is keeping the mobile avatar functional even when individual sensors are temporarily or permanently disabled or its temporal or spatial resolution is decreased. “Users need to be informed and aware that robot functionalities may be limited in such cases.”

The interfaces developed as part of the project will ultimately be integrated into a larger mobile robot control system, in collaboration with our partners. These “low-data” robots could be used in museums and for other applications beyond the school context.