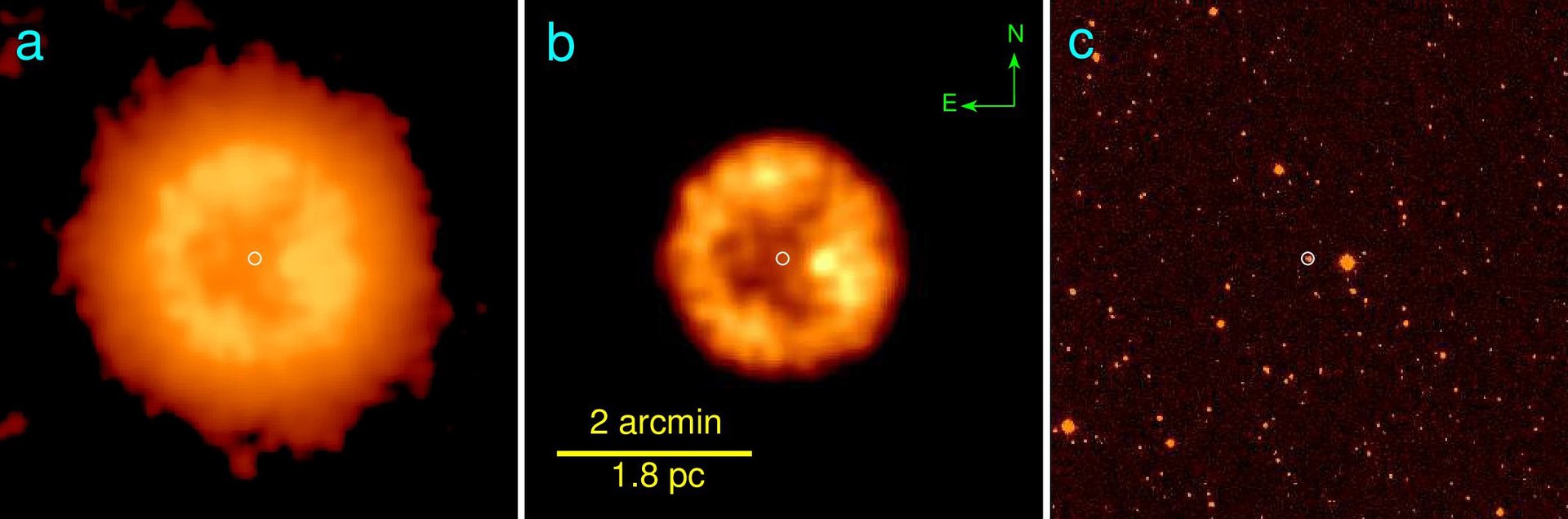

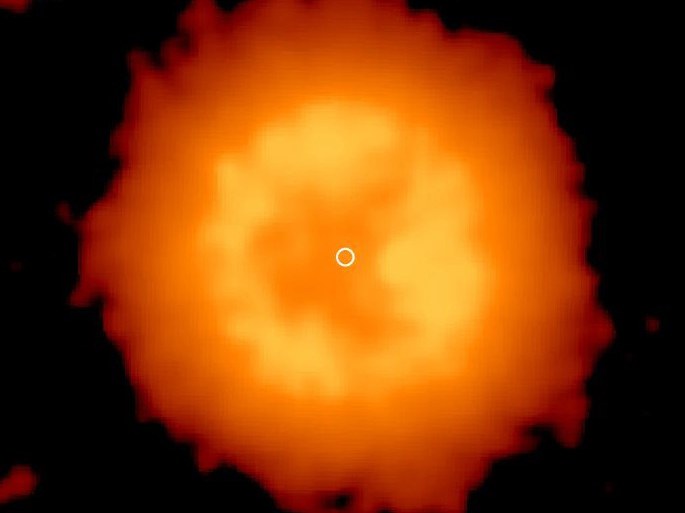

The extremely rare merger product was discovered by scientists from the University of Moscow. On images made by the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) satellite they found a gas nebula with a bright star in its center. Surprisingly, however, the nebula emitted almost exclusively infrared radiation and no visible light. "Our colleagues in Moscow realized that this already argued for an unusual origin", explains Dr. Götz Gräfener from the Argelander Institute for Astronomy (AIfA) at the University of Bonn.

In Bonn, the spectrum of the radiation emitted by the nebula and its central star was analyzed. In this way, the AIfA researchers were able to show that the enigmatic celestial object contained neither hydrogen nor helium - a characteristic typical for the interiors of white dwarfs. Stars like our Sun generate their energy through hydrogen burning, the nuclear fusion of hydrogen. When the hydrogen is consumed, they continue burning helium. However, they cannot fuse even heavier elements - their mass is insufficient to produce the necessary high temperatures. Once all helium is used up, they cease burning and cool down turning into so-called white dwarfs.

Usually their life is over at this point. But not for J005311 – this is how the scientists named their new find in the constellation Cassiopeia, 10,000 light-years from Earth. "We assume that two white dwarfs formed there in close proximity many billions of years ago," explains Prof. Dr. Norbert Langer from AIfA. "They circled around each other, creating exotic distortions of space-time, called gravitational waves." In the process, they gradually lost energy. In return, the distance between them shrunk more and more until they finally merged.

Only five of these objects in the Milky Way

Now their total mass was sufficient to fuse heavier elements than hydrogen or helium. The stellar furnace started burning again. "Such an event is extremely rare," stresses Gräfener. "There are probably not even half a dozen such objects in the Milky Way, and we have discovered one of them."

An extreme stroke of luck. Nevertheless, the researchers are convinced that they are right with their interpretation. For one, the star in the center of the nebula shines 40,000 times as bright as the sun, far brighter than a single white dwarf could. In addition, the spectra indicate that J005311 has an extremely strong stellar wind - this is the stream of material that emanates from the stellar surface. Its engine is the radiation generated during the burning process. Only, at a speed of 16,000 kilometers per second, the wind of J005311 is so fast that this factor alone is not enough to explain it. However, merged white dwarfs are expected to have a very strong rotating magnetic field. "Our simulations show that this field acts like a turbine, which additionally accelerates the stellar wind," says Gräfener.

Sadly, the resurgence of J005311 will not last long. In only a few thousand years the star will have transformed all elements into iron and fade again. As its mass has increased to more than 1.4 times the mass of the Sun in the merger process, it will suffer an exceptional fate. The star will collapse under the influence of its own gravity. At the same time, the electrons and protons building up its matter will fuse into neutrons. The resulting neutron star has only a fraction of its previous size, measuring only few kilometers in diameter, while it is weighing more than the entire solar system.

J005311, however, won’t leave without a final salute. Its collapse will be accompanied by a huge bang, a so-called supernova explosion.

Publication: Vasilii V. Gvaramadze, Götz Gräfener, Norbert Langer, Olga V. Maryeva, Alexei Y. Kniazev, Alexander S. Moskvitin & Olga I. Spiridonova: A massive white-dwarf merger product before final collapse; Nature, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1216-11

Contact:

Dr. Götz Gräfener

Argelander Institute for Astronomy at the University of Bonn.

Tel. +49-(0)228/733651

E-mail: goetz@astro.uni-bonn.de

Prof. Dr. Norbert Langer

Argelander Institute for Astronomy at the University of Bonn.

Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy

Tel. +49-(0)228/733656

E-mail: nlanger@astro.uni-bonn.de