Your paper addresses proxy measures and proxy failure. Could you briefly introduce the topic?

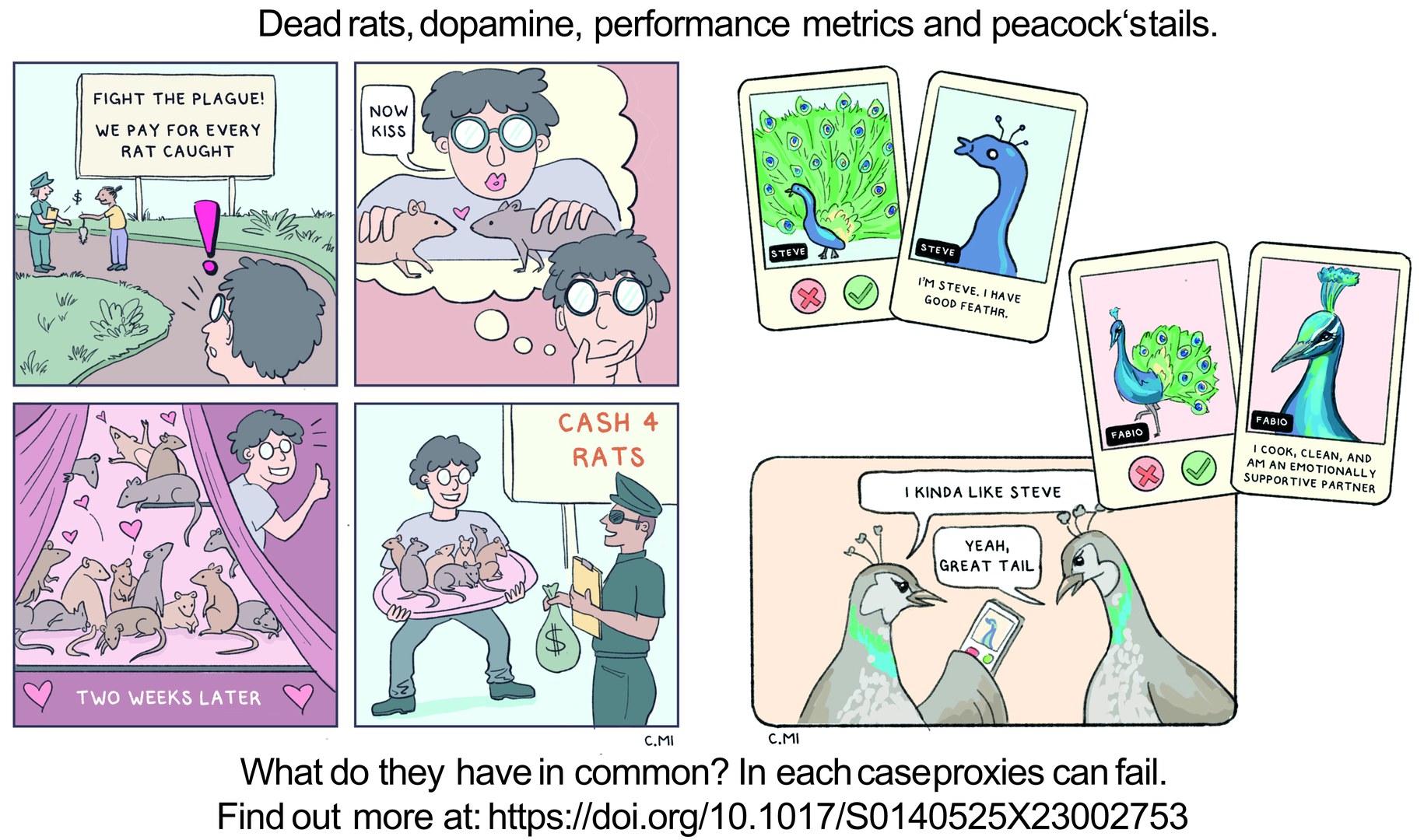

A proxy measure is an indicator, which is used because the actual underlying goal cannot be perfectly assessed. For instance, test scores are intended to measure knowledge (or teaching quality). But students or teachers might find ways to improve test scores without actually increasing knowledge. If this happens, the measure stops measuring the goal it was designed to measure. This phenomenon is sometimes called ‘Goodhart‘s Law’: “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.” But the underlying phenomenon has been observed again and again, and has received numerous names.

This raises the question: Why is it so common?

That is exactly the question that drove us. We started by collecting all the different contexts in which the phenomenon has been described. Charles Goodhart, an economist and name giver of the eponymous law, studied the phenomenon in the context of macroeconomic indicators. At about the same time ‘Campbell‘s Law’ was coined to describe the phenomenon in the context of education and other social domains. The list could go on, but the interesting thing is that we kept finding more instances and versions of what seemed like the same key phenomenon. What really caught my interest was when I read the article of two Harvard Ecologists who outlined how the same principle occurs in biology.

How does Campbell’s Law apply to biology?

According to ‘runaway signalling theory’ peacocks, for instance, advertise their fitness as mates via their opulent tails. But how did such opulent plumage arise evolutionarily? The theory suggests that the peacock tails may have initially been a useful ‘signal’ for the fitness of a male. Birds with larger tails were preferred by peahens. But this preference of the peahens led to an evolutionary arms race, in which the size of peacock tails exploded - until its fitness disadvantages outweighed its sexual advantages. The prominent ecologist Richard Prum from Yale argues that such runaway processes are the reason birds evolved at all, since they help to explain the evolution of feathers. Peacocks don’t intentionally cheat when being judged by peahens. But the same inflationary dynamic emerges. The same has been observed in AI research.

Why is artificial intelligence (AI) also prone to such proxy-based distortions?

The algorithm on which an AI is based must somehow measure what ‘good performance’ is. This is typically done by coding a so called ‚ ‘loss function’ or ‘objective function’, which can be calculated for every input. The option with the best value is then chosen or used. This may be the results of a search engine or ChatGPT™ or the recommendations in social media. The key point is that this ‘objective function’ is by definition a proxy measure of what we really want the AI to do. In practice, it appears to often be impossible to fully capture complex human goals mathematically. For this reason, proxy failure is a central topic in current AI-safety research.

Do you have an example?

The AI-researcher and philosopher Nick Bostrom develops a scenario in which the managers of a paperclip factory use an AI to maximize production. This AI is so advanced that it optimizes not only production but also its own code, leading it to become a ‘superintelligence’. Such a superintelligence would still just maximize its programmed goal, namely the proxy measure, but it would be unbelievably effective. It would, according to Bostrom, turn the entire world into a giant paperclip factory and enslave all of humanity (including the original managers).

This hypothetical scenario is particularly vivid, but there are now numerous examples of proxy-based AI algorithms doing real harm: for instance, when an AI used to evaluate creditworthiness systematically denies credit to minorities, leading to litigation for discrimination.

Did such proxy failures also happen in the past?

A well-documented example is the following: The French government of colonial Hanoi decided to fight a rat plague by remunerating citizens for killing rats. Specifically, rat catchers received a reward for every rat tail they delivered, in order to prove they had removed a rat from the city’s sewers. But soon rats without tails were seen scurrying through the city, presumably left alive to breed and provide more valuable tails. Particularly enterprising individuals even set up rat farms.

Is Campbell’s Law universal?

In our article we systematically examine the commonalities and differences between all these cases. We conclude that there is a fundamental information- or control-theoretical principle at work: the use of proxy measures creates a ‘pressure’ which pushes the measure away from its underlying goal. But this pressure doesn’t necessarily lead to the measure becoming useless. Much of our work examines the mechanisms that mitigate or constrain proxy failure. Competitive markets are one such mechanism: a firm that produces unusable products due to some internal failure of ‘performance indicators’ would simply not survive market selection. Managers thus know the problem well. They know that if they don’t stay attentive, and keep proxy failure at bay, their job would be at risk.

Firms have to stay profitable. Is this an effective mechanism to limit proxy failure?

In principle it is. But it is important to remember that ‘consumption’ and ‘profit’ are also just proxy measures. According to standard economic theory, they measure welfare. But in light of increasingly dramatic ecological crises, the question whether the unrestricted maximization of economic proxy measures truly maximizes long term welfare is increasingly being voiced. Prominent Economists such as Maja Göpel or Kate Raworth have a clear answer: no. We need to mitigate a proxy failure of our entire economies, a ‘market failure’, for instance by levying carbon taxes or similar measures.

The focus on proxy measures resembles a kind of tunnel vision. How can be remove our ‘blinders’?

A natural question. Unfortunately, the answer is somewhat unsatisfactory. One of the key insights of our work is that we will never be able to fully remove the blinders. In practice proxy measures are simply unavoidable. This is due to several fundamental limitations, which affect all decision systems, be it a human, an animal or a machine. For instance, decisions almost inevitably have to be based on incomplete information: we can’t look into the heads of students.

How then can we achieve better regulation of complex systems? By combining several proxy measures?

A combination of several proxy measures is indeed almost always useful, particularly if they measure different aspects of the underlying goal. It can help avoid a situation in which the optimization of one proxy measure undermines something that is measured by the second proxy measure. If we find a third unanticipated aspect is undermined, we can add a third proxy that measures it. Such dynamics indeed seem to recur across biological and social systems – it was recently christened the ‘proxy treadmill’. Accordingly, proxy-based systems tend to increase in complexity over time. To some degree, this seems inevitable.

Where’s the sweet spot?

Ever more complex measurement and control systems also cost time and resources. The historian Jerry Muller describes this in detail in his book ‘The Tyranny of Metrics’. Accordingly, the impulse to always add indicators and competition can lead to a ‘mushroom like growth of administrative staff’. I hear my father speaking. He worked in a hospital for many years and observed with dismay how the ratio of medical to administrative staff seemed to keep tilting towards the latter as years went by. In attempting to measure and control everything doctors do, and simultaneously avoid proxy failure, less and less time and money remains for the original purpose of the hospital – treating patients. All the time is spent doing paperwork. Muller argues that at some point we must resist the impulse to regulate and control behavior. In practice this means less competition, fewer proxy measures, and a greater focus on the employees’ intrinsic motivation to do their job.

What led you to this topic?

I first started working on the problem in the context of ‘meta-sciences’. That is the study of the academic system itself. Many researchers are worried that the extreme competition in academia is adversely affecting scientific quality. The evaluation of scientists based on ‘publication measures’ is a key area of concern. For instance, I developed a mathematical model that makes concrete predictions about how ‘proxy failure’ should be detectable in published sample sizes. Sample sizes in some disciplines have been known since the 60s to be too small to provide accurate results. But even though researchers have been trying to call attention to this problem for just as long, the problem to persists. Proxy-based selection seems to be a key reason.

What are the next steps for your article?

The journal `Behavioral and Brain Sciences´, where the paper has been published, maintains an innovative scientific discussion format. First the paper is formally peer reviewed, and then published as a preprint. Then researchers across disciplines can submit commentary and criticism of the work. The editors select an interesting and diverse set of commentaries to be published alongside the original article in the final version. I think this is a fantastic format, because it allows us to collect both supportive and critical perspectives on a topic in one place. Our article points to several implications that are already controversially discussed in the respective disciplines. But I’m also curious to see if authors from other disciplines or areas of life will point us to completely novel instances of the phenomenon.

Can everyone participate?

Unfortunately the commentary submission phase is now closed (as of August 10th, 2023)

How will you substantiate your findings?

In our view the findings are already pretty solid. In almost every one of the disciplines we review, the fundamental principles are well accepted, and only details remain controversial. What is new is that we bring all these different phenomena together. The next step will be to delve deeper into the various mathematical models that have been proposed within distinct disciplines and see if these too can be unified.

About the person:

Oliver Braganza, born 1984 in Fulda, Germany, studied human biology and molecular biomedicine in Marburg and Bonn. Following his dissertation at the Institute for Experimental Epileptology and Cognition Research he continued to investigate neural circuits and started researching proxy failure in academia. He is a member of the excellence cluster ImmunoSensation2, the transdisciplinary research areas ‘Life and Health’, ‘Individuals and Societies’, as well as ‘Modeling’ and at the Center for Science and Thought at the University of Bonn.