Suppose you observe a waiter (the lockdown is already history) who on New Year's Eve has to serve an entire tray of champagne glasses just a few minutes before midnight. He rushes from guest to guest at top speed. Thanks to his technique, perfected over many years of work, he nevertheless manages not to spill even a single drop of the precious liquid.

A little trick helps him to do this: While the waiter accelerates his steps, he tilts the tray a bit so that the champagne does not spill out of the glasses. Halfway to the table, he tilts it in the opposite direction and slows down. Only when he has come to a complete stop does he hold it upright again.

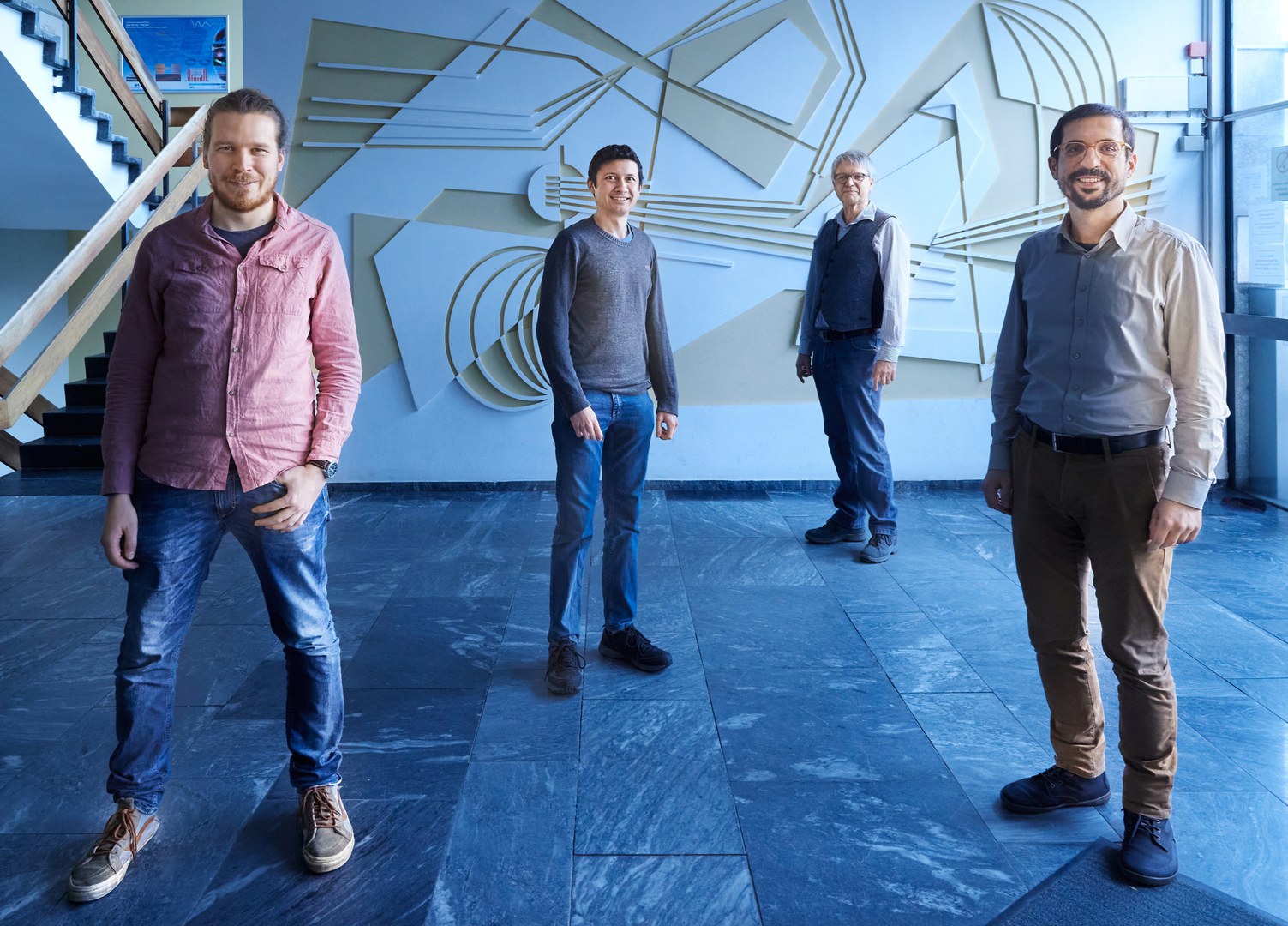

Atoms are in some ways similar to champagne. They can be described as waves of matter, which behave not like a billiard ball but more like a liquid. Anyone who wants to transport atoms from one place to another as quickly as possible must therefore be as skillful as the waiter on New Year's Eve. "And even then, there is a speed limit that this transport cannot exceed," explains Dr. Andrea Alberti, who led this study at the Institute of Applied Physics of the University of Bonn.

Cesium atom as a champagne substitute

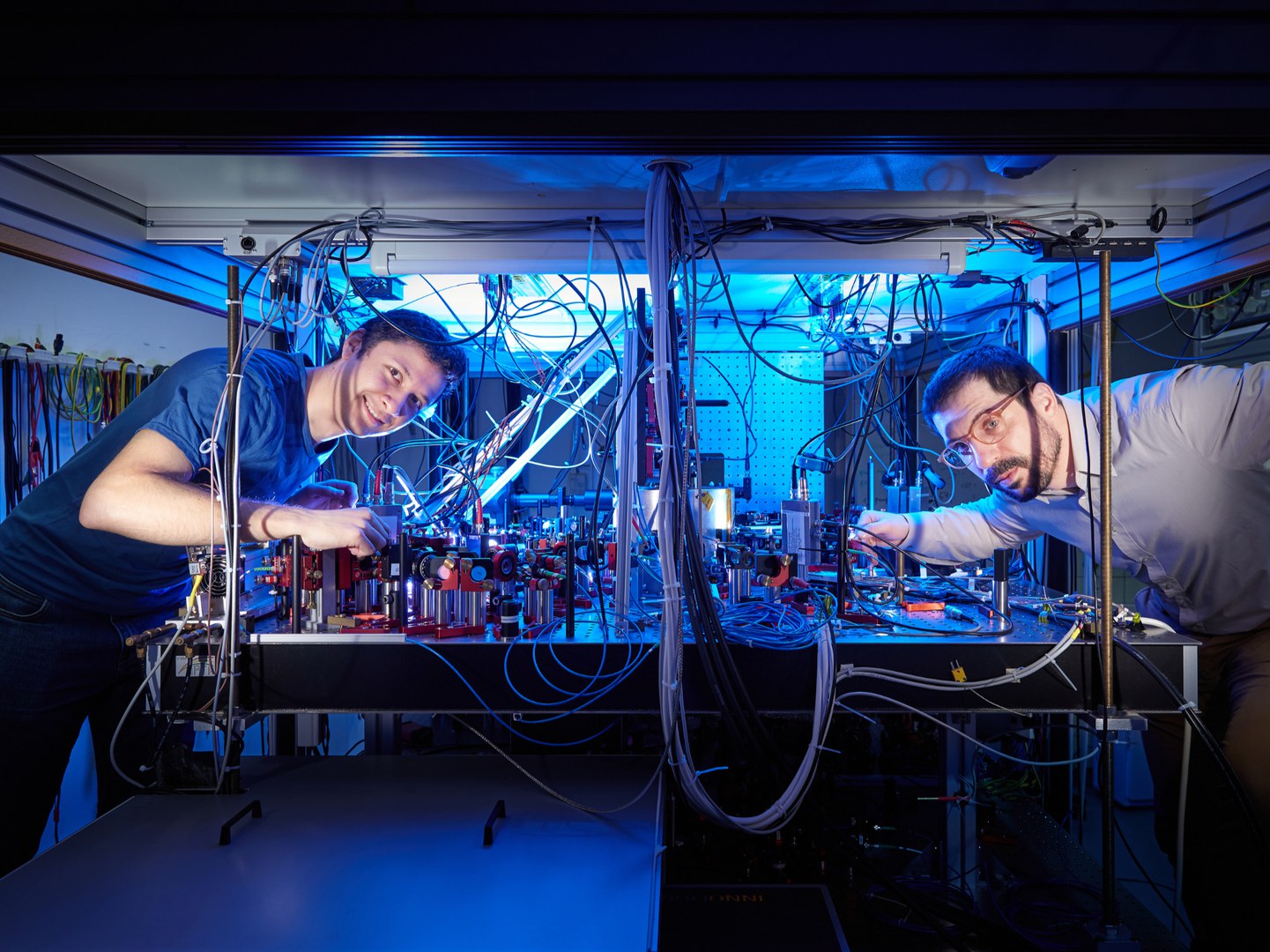

In their study, the researchers experimentally investigated exactly where this limit lies. They used a cesium atom as a champagne substitute and two laser beams perfectly superimposed but directed against each other as a tray. This superposition, called interference by physicists, creates a standing wave of light: a sequence of mountains and valleys that initially do not move. "We loaded the atom into one of these valleys, and then set the standing wave in motion – this displaced the position of the valley itself," says Alberti. "Our goal was to get the atom to the target location in the shortest possible time without it spilling out of the valley, so to speak."

The fact that there is a speed limit in the microcosm was already theoretically demonstrated by two Soviet physicists, Leonid Mandelstam and Igor Tamm more than 60 years ago. They showed that the maximum speed of a quantum process depends on the energy uncertainty, i.e., how "free" the manipulated particle is with respect to its possible energy states: the more energetic freedom it has, the faster it is. In the case of the transport of an atom, for example, the deeper the valley into which the cesium atom is trapped, the more spread the energies of the quantum states in the valley are, and ultimately the faster the atom can be transported. Something similar can be seen in the example of the waiter: If he only fills the glasses half full (to the chagrin of the guests), he runs less risk that the champagne spills over as he accelerates and decelerates. However, the energetic freedom of a particle cannot be increased arbitrarily. "We can't make our valley infinitely deep – it would cost us too much energy," stresses Alberti.

Beam me up, Scotty!

The speed limit of Mandelstam and Tamm is a fundamental limit. However, one can only reach it under certain circumstances, namely in systems with only two quantum states. "In our case, for example, this happens when the point of origin and destination are very close to each other," the physicist explains. "Then the matter waves of the atom at both locations overlap, and the atom could be transported directly to its destination in one go, that is, without any stops in between – almost like the teleportation in the Starship Enterprise of Star Trek."

However, the situation is different when the distance grows to several dozens of matter wave widths as in the Bonn experiment. For these distances, direct teleportation is impossible. Instead, the particle must go through several intermediate states to reach its final destination: The two-level system becomes a multi-level system. The study shows that a lower speed limit applies to such processes than that predicted by the two Soviet physicists: It is determined not only by the energy uncertainty, but also by the number of intermediate states. In this way, the work improves the theoretical understanding of complex quantum processes and their constraints.

The physicists' findings are important not least for quantum computing. The computations that are possible with quantum computers are mostly based on the manipulation of multi-level systems. Quantum states are very fragile, though. They last only a short lapse of time, which physicists call coherence time. It is therefore important to pack as many computational operations as possible into this time. "Our study reveals the maximum number of operations we can perform in the coherence time," Alberti explains. "This makes it possible to make optimal use of it."

Funding:

The study was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) as part of the Collaborative Research Center SFB/TR 185 OSCAR. Funding was also provided by the Reinhard Frank Foundation in collaboration with the German Technion Society, and by the German Academic Exchange Service.

Publication: Manolo R. Lam, Natalie Peter, Thorsten Groh, Wolfgang Alt, Carsten Robens, Dieter Meschede, Antonio Negretti, Simone Montangero, Tommaso Calarco und Andrea Alberti: Demonstration of Quantum Brachistochrones between Distant States of an Atom; Physical Review X; https://journals.aps.org/prx/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevX.11.0110351

Contact:

Dr. Andrea Alberti

Institut für Angewandte Physik der Universität Bonn

Tel. +49 228 73-3471

E-mail: alberti@iap.uni-bonn.de