Normally, fat cells store energy. In brown fat cells, however, energy is dissipated as heat - brown fat thus serves as a biological heater. Most mammals therefore have this mechanism. In humans it keeps newborns warm, in human adults, brown fat activation positively correlates with cardio-metabolic health.

"Nowadays, however, we're toasty warm even in winter," explains Prof. Dr. Alexander Pfeifer from the Institute of Pharmacology and Toxicology at the University Hospital Bonn. "So our body's own furnaces are hardly needed anymore." At the same time, we are eating an increasingly energy-dense diet and are also moving far less than our ancestors. These three factors are poison for brown fat cells: They gradually cease to function and eventually even die. On the other hand, the number of severely overweight people worldwide continues to increase. "Research groups around the world are therefore looking for substances that stimulate brown fat and thus increase fat burning," says Pfeifer.

Dying fat cells boost energy combustion of their neighbors

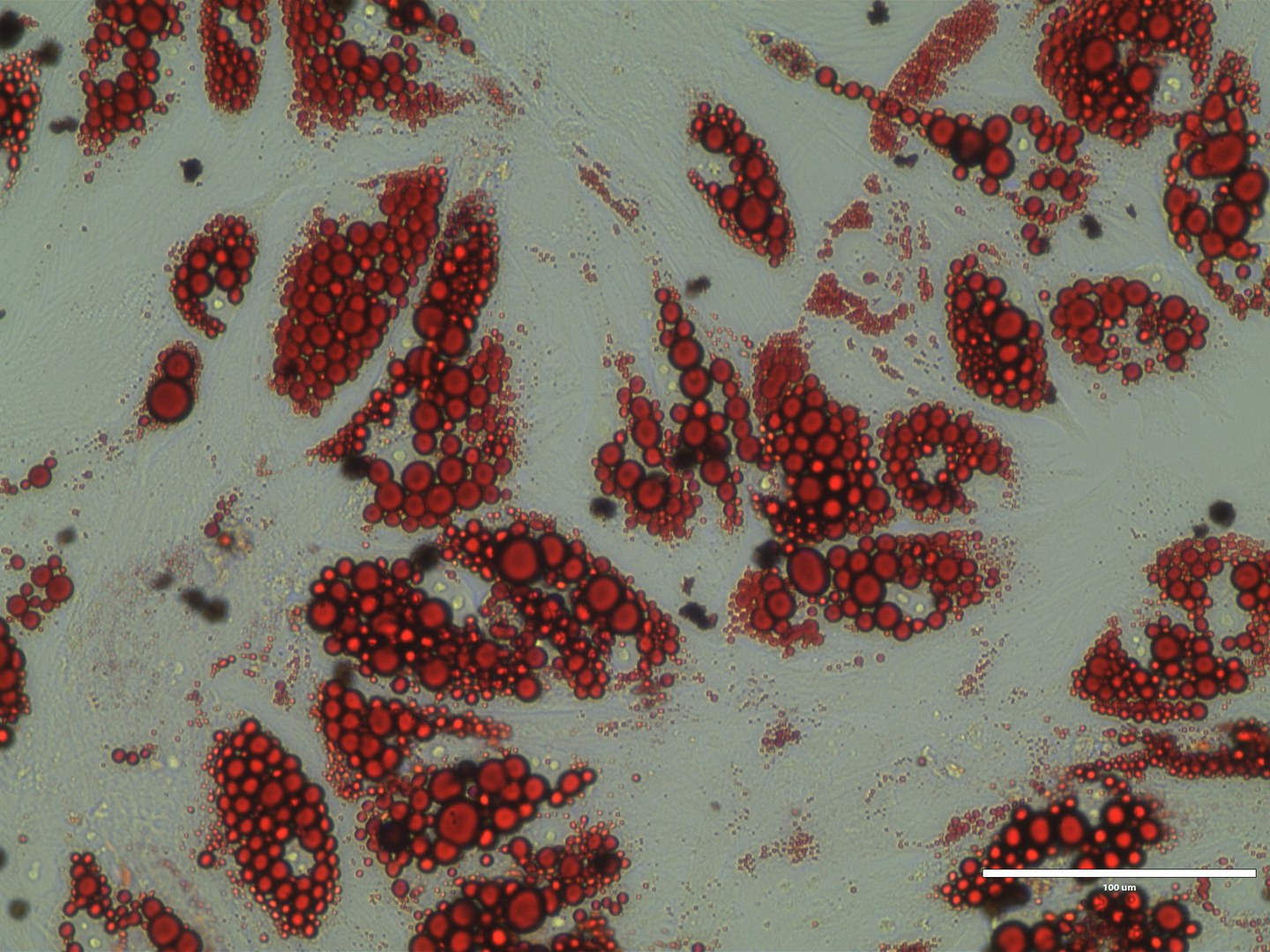

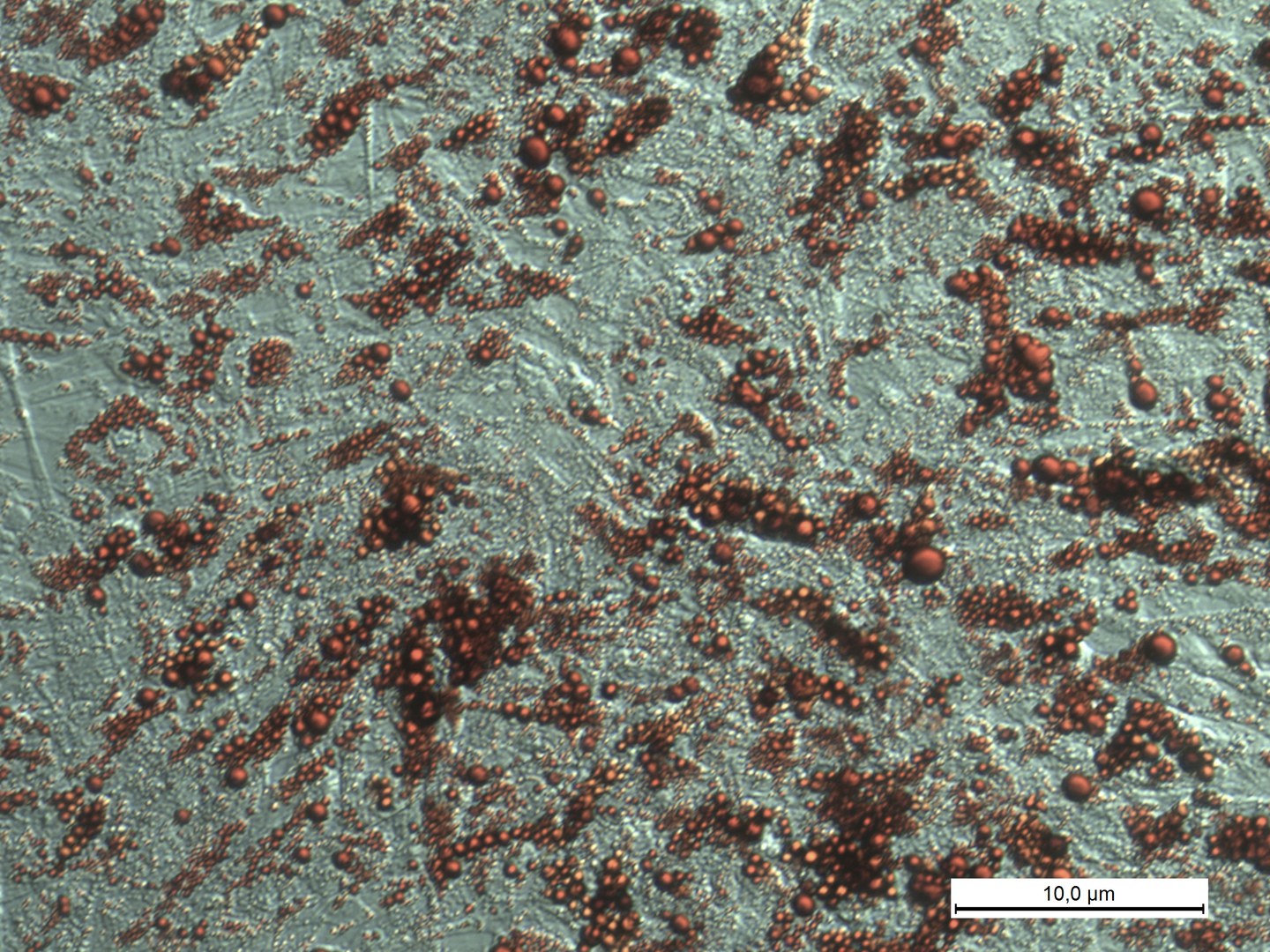

Together with a group of colleagues, the team at the University of Bonn has now identified a key molecule named inosine that is capable of burning fat. "It is known that dying cells release a mix of messenger molecules that influence the function of their neighbors," explains Dr. Birte Niemann from Pfeifer's research group. Together with her colleague Dr. Saskia Haufs-Brusberg, she planned and conducted the central experiments of the study. "We wanted to know if this mechanism also exists in brown fat."

The researchers therefore studied brown fat cells subjected to severe stress, so that the cells were virtually dying. "We found that they secrete the purine inosine in large quantities," Niemann says. More interesting, however, was how intact brown fat cells responded to the molecular call for help: They were activated by inosine (or simply by dying cells in their vicinity). Inosine thus fanned the furnace inside them. White fat cells also converted to their brown siblings. Mice fed a high-energy diet and treated with inosine at the same time remained leaner compared to control animals and were protected from diabetes.

The inosine transporter seems to play an important role in this context: This protein in the cell membrane transports inosine into the cell, thus lowering the extracellular concentration. Therefore, inosine can no longer exert its combustion-promoting effect.

Drug inhibits the inosine transporter

"There is a drug that was actually developed for coagulation disorders, but also inhibits the inosine transporter," says Pfeifer, who is also a member of the Transdisciplinary Research Areas "Life and Health" and "Sustainable Futures" an the ImmunoSensation2 Cluster of Excellence at the University of Bonn.

"We gave this drug to mice, and as a result they burned more energy." Humans also have an inosine transporter. In two to four percent of all people, it is less active due to a genetic variation. "Our colleagues at the University of Leipzig have genetically analyzed 900 individuals," Pfeifer explains. "Those subjects with the less active transporter were significantly leaner on average."

These results suggest that inosine also regulates thermogenesis in human brown fat cells. Substances that interfere with the activity of the transporter could therefore potentially be suitable for the treatment of obesity. The drug already approved for coagulation disorders could serve as a starting point. "However, further studies in humans are needed to clarify the pharmacological potential of this mechanism," Pfeifer says. Neither does he believe that a pill alone will be the solution to the world's rampant obesity pandemic. "But the available therapies are not effective enough at the moment," he stresses. "We therefore desperately need medications to normalize energy balance in obese patients."

The key role played by the body's own heating system is also demonstrated by a major new joint research consortium: The German Research Foundation (DFG) recently approved a Transregional Collaborative Research Center in which the Universities of Bonn, Hamburg and Munich conduct targeted research on brown adipose tissue.

Funding:

The University of Bonn as well as the University Hospital Bonn, the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, the University as well as the University Hospital Leipzig, the Helmholtz Center Munich and the University of Texas were involved in the study. The work was funded by the German Research Foundation and the National Institute of Health (USA).

Publication: Birte Niemann et al.: Apoptotic brown adipocytes enhance energy expenditure via extracellular inosine; Nature; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05041-01