River blindness (onchocerciasis) is most common in Africa and Central and South America. Bloodsucking blackflies pick up worm larvae from infected people and spread them further. These develop into sexually mature nematodes, which take up residence as parasites in the connective tissue and produce so-called microfilariae. If the eyes are affected, this can lead to blindness. The term "river blindness" can be traced back to the fact that the disease accumulates near flowing waters because this is where the larvae of the blackfly are found.

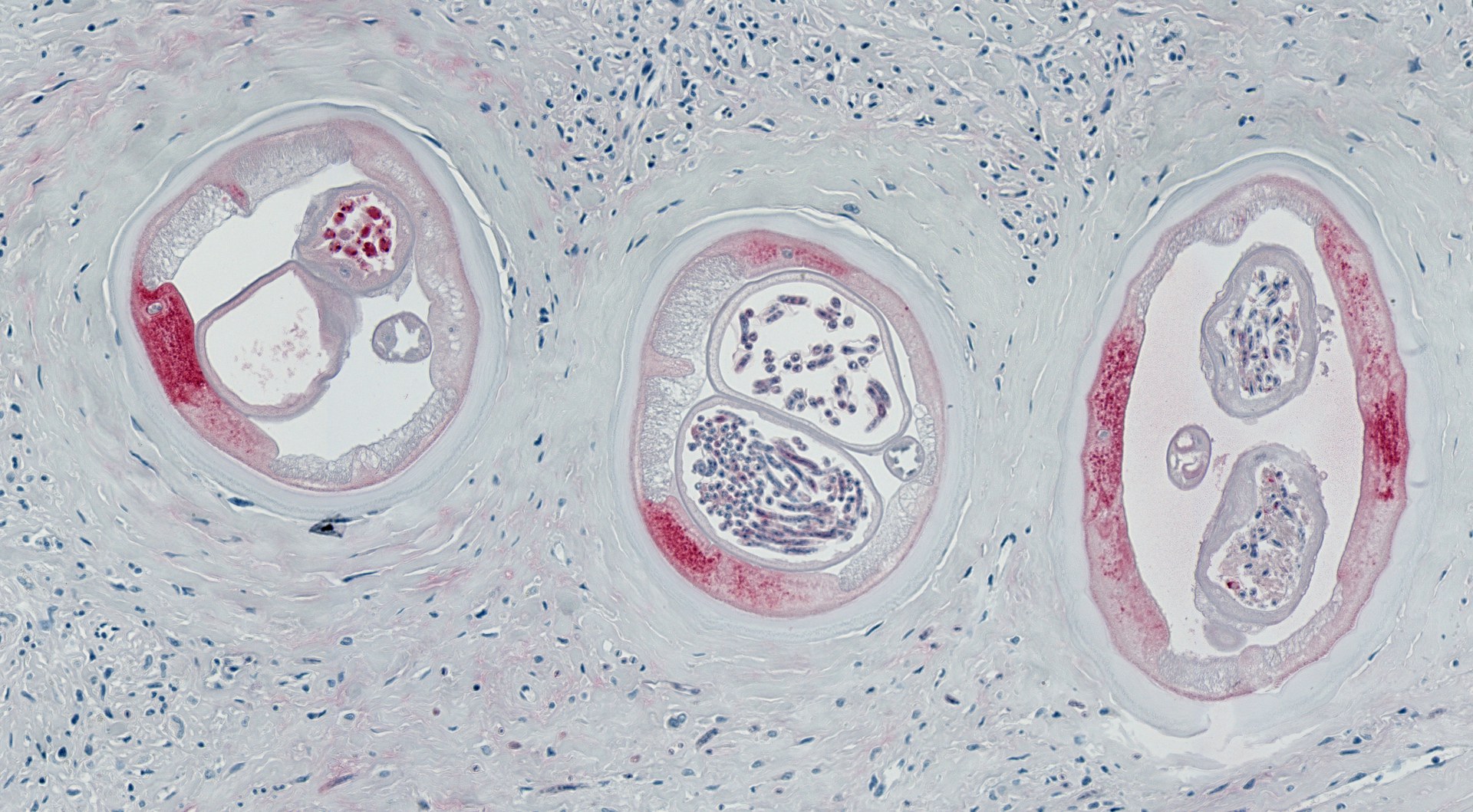

The adult female worms, up to 30 centimeters long, usually live in nodules (onchocercomes) in the subcutis; they are fertilized by males that migrate around in the body. In the onchocercomes, the females bear worm larvae (microfilariae). "This whole process can be detected under the microscope by looking at histological samples," says Prof. Dr. Achim Hörauf, director of the Institute for Medical Microbiology, Immunology and Parasitology (IMMIP) at the University Hospital Bonn (UKB). The effect of new drugs that can inhibit or kill the worms at different stages must therefore also be confirmed using histological samples.

Artificial intelligence replaces examinations "by hand"

Previously, these histological examinations for river blindness were performed manually. "However, it is better for the approval of new drugs if the quality of the examination can be standardized by means of artificial intelligence," says Hörauf. Tissue sections previously evaluated by several experts are used to train AI models and verify the accuracy of the automatic evaluation.

"The advantage of artificial intelligence, in addition to standardization, is that automated evaluation of histological cross-sectional images is much faster than would be possible manually. In some cases, this can shorten the evaluation of clinical studies by months," says Dr. Daniel Kühlwein of the AI Center of Excellence at IT consultancy Capgemini, which is developing the algorithms.

"Dr. Ute Klarmann-Schulz and Dr. Janina Kühlwein from IMMIP have contributed significantly to the execution of the work to date and the application process," says Hörauf, who is also a member of the Cluster of Excellence Immunosensation2 and the Transdisciplinary Research Area (TRA) "Life and Health" at the University of Bonn. One of the TRA’s main topics is to support research at the nexus point of biomedicine and artificial intelligence. Also involved is the Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative (DNDi) in Geneva, which will evaluate AI results as part of regulatory trials for new drugs for river blindness. "It would be a great success for our team if we could contribute to the fight against onchocerciasis in this way," adds Klarmann-Schulz.

The researchers at UKB had already received a seed grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, which demonstrated the project's feasibility in principle. Following this, the Gates Foundation invited the Bonn researchers to apply for further funding. "Since no drug has yet been developed that targets adult filarial worms, we are breaking new ground here," Hörauf says. Drugs approved so far only kill the worm larvae. Researchers at IMMIP have discovered several new agents for the treatment of river blindness to date and have been involved in the preclinical development of these agents.

"The Faculty of Medicine of the University of Bonn is delighted that the researchers of the Institute of Medical Microbiology, Immunology and Parasitology have been awarded this grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation," says Dean Prof. Dr. Bernd Weber. "This strengthens the international visibility of Bonn as a location in connection with the fight against neglected tropical diseases."