It is often said that there are two sides to every story, and this applies both literally and figuratively to the Egyptian Museum’s Bonn Limestone Tablet with shelf mark BoSAe 2113. This is because the two sides of the tablet, which is probably well over 3,000 years old, bear vastly different designs, and it is precisely this that links them both together. Put another way, they only provide an academically satisfactory answer to the question of how this object might have been used when they are considered as two parts of a whole.

“The double-sidedness of the small stele was no secret,” explains Prof. Dr. Ludwig Morenz from the University of Bonn’s Egyptology team, who is also a member of the Bonn Center for Dependency and Slavery Studies (BCDSS) Cluster of Excellence and the Present Pasts Transdisciplinary Research Area at the University. However, it was not until he was working on the BMBF’s collaborative project “SiSi” (“Sinnüberschuss und Sinnreduktion von, durch und mit Objekten. Materialität von Kulturtechniken zur Bewältigung von Außergewöhnlichem,” or “Excess of meaning and reduction of meaning by, through and with objects. The materiality of cultural techniques for coping with exceptional events”) that he succeeded in finding a new angle on the limestone tablet’s sacred content relating to how people deal with crises.

The upside-down lion’s head

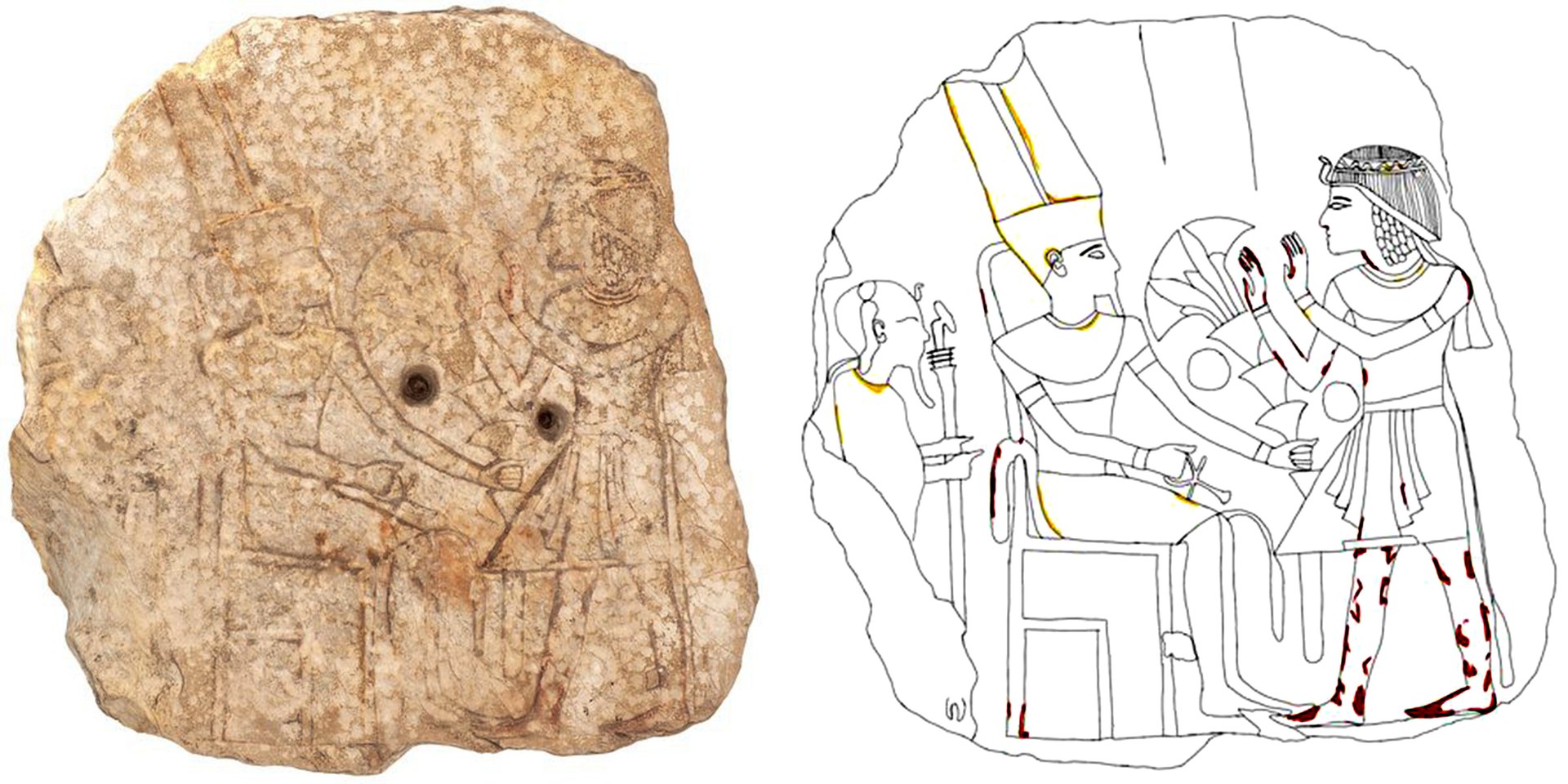

The stele was a kind of votive offering, Morenz explains. Professor Alfred Wiedemann, the founding father of Egyptology in Bonn in the early 20th century, had acquired the stone tablet in Luxor, the ancient city of Thebes. This makes it easy to place in its art history and religious studies context. The relief on the relatively flat front side of the limestone tablet is finely crafted and full of detail. In aesthetic terms, it is the “pretty” side of the tablet.

Putting the fragmentary image back together reveals a representation of the Ancient Egyptian gods Amun and Khonsu and a royal figure who is approaching them: a pharaoh performing a sacrifice. Engaged in prayer, he is also playing the role of mediator between the gods and the people. “This supports the assumption that this is a religious object, especially since a god-and-king scene like this is typical of the time from which the stone tablet dates,” says Morenz.

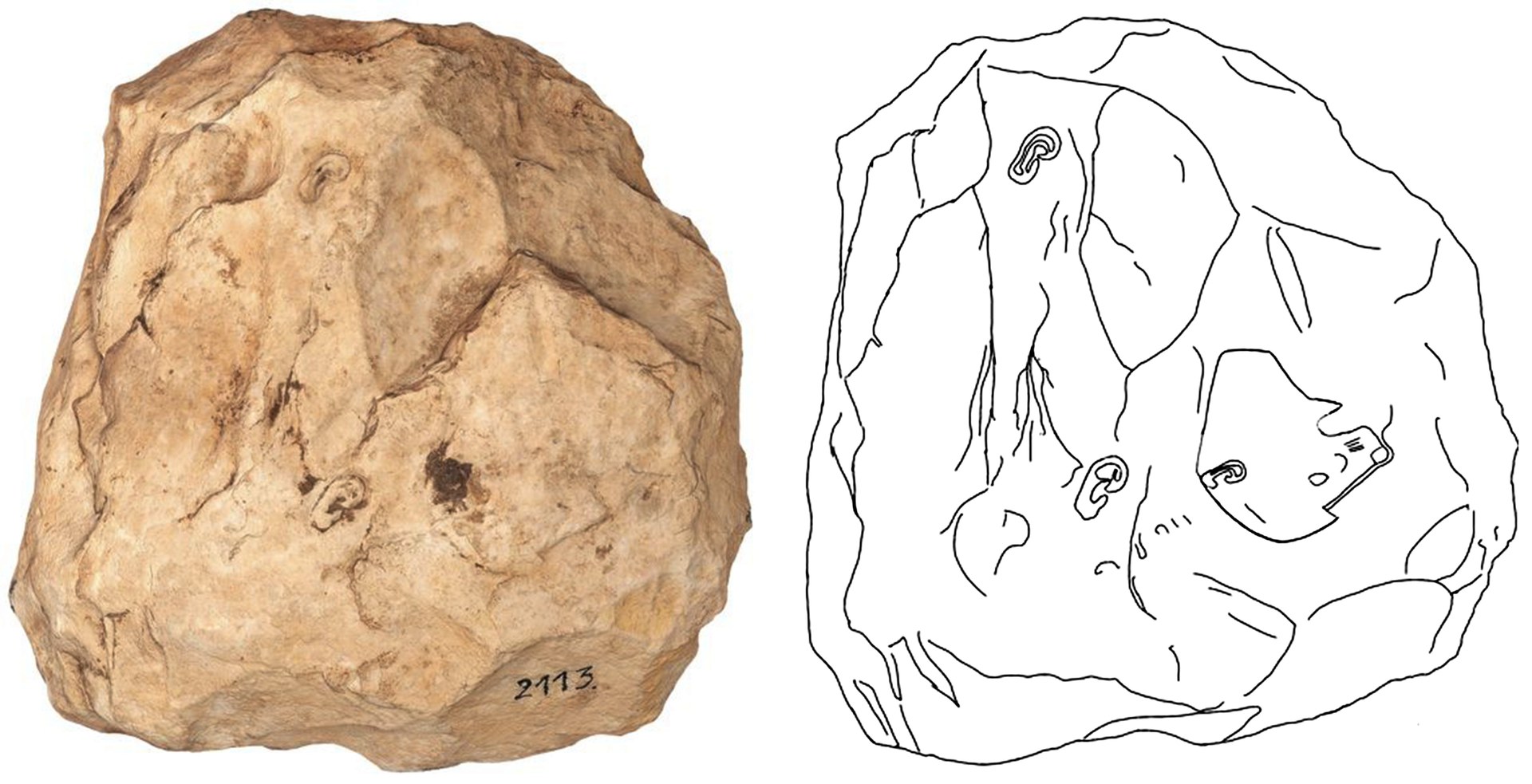

However, one particular detail left him perplexed when he examined it more closely: although the representation is ostensibly of the Theban triad of deities Amun, Mut and Khonsu, the goddess Mut is missing. “The three deities are usually depicted together as a family,” Morenz explains. He admits that this obvious, even downright deliberate omission from the representation had irked him, and it is also echoed in the title of his book: “Wo bleibt Mut?” (“Where Is Mut?”). To find the answer, one needs to look more closely at the rough back side, because it too contains illustrations: clearly visible are three distinctively carved human ears and a much larger lion’s head rotated through 180 degrees.

In the Egyptian pantheon, a lion’s head symbolized the goddess Mut. “Mut assumes the role of divine mother,” the Egyptologist says, explaining her significance. She represents a kind of powerful aggressiveness, he adds, but undoubtedly in a good way: “Mut embodies power and strength and is therefore often invoked to provide protection.” If one interprets the lion’s head as representing the goddess Mut, therefore, the divine family is once again complete. The three ears, meanwhile, lend further support to the idea of an invocation or dialogue between a human being and their god. Their number - three - matches the triad of deities and, in a religious studies context, also chimes in with the pharaoh being shown as mediator on the other side.

An expression of personal piety

All of these indications are strong signs of the relationship between human and god that is expressed on this stone tablet. What is particularly fascinating for Morenz here is the interplay between official religion (on the front) and personal piety or private religion (on the back). This is because he thinks it highly plausible that someone would pray to the goddess Mut in times of great need and emergency to ask her to hear and assist them. It is a welcome discovery as far as the University of Bonn is concerned since, in this stone tablet, it possesses a “masterpiece” in Morenz’s words that gives us a very good idea on closer inspection of how people in Ancient Egypt coped with crises.