Did you get the samples you need?

The expedition was highly successful; we definitely secured enough samples for a few years of intriguing research. During a voyage like this one, minor setbacks or problems will always arise requiring adjustment of the planning. But the samples ultimately obtained from such a remote region are all worth their weight in gold, so I am really looking forward to doing some lab work on this material!

What will you do with the data you gathered during the expedition?

This expedition was all about collecting samples for our working group at the University of Bonn, so once we are back home in Bonn the samples will be analyzed in the lab, generating data. I am bringing two different types of samples home from Greenland: frozen sediment samples and pore water samples (water from sediments). So there are all kinds of things we can do in the lab, and we’ll be doing lots of different analyses. Other institutes are conducting different measurements, so collaboration with my colleagues on the expedition will be an important part of our future activities. The resulting data will be published at the end of this process.

When will results be available?

It depends entirely on the type of analysis concerned, whether sooner or later. The initial results will probably be out in a few months. But the kinds of samples taken and thus the data generated by each individual team member are very different in nature, so it can take quite a while for a clear and conclusive picture to emerge. The samples and data are extremely valuable, so we take our time in order to get a really thorough analysis. This process can take several years!

What will you do once you get back on land?

I’ll probably take a few days off to spend some time with family and friends. I’ll have to get used to summer temperatures again, back in Germany. I’m especially looking forward to having an ice cream on the banks of the Rhine, and I want a really good salad too… After so many weeks at sea, we’re running low on fresh fruit and vegetables! After that I’ll be heading straight for the lab. I can’t wait to see the data that the samples will yield, the initial findings will be very exciting.

What is the ship’s own climate footprint, and why was the decision made to voyage by ship?

The Sir David Attenborough is a newly built vessel specially designed for sustainability. The efficiency and other sustainability factors important in its construction thus come into play in its operation, but nevertheless, operating such a large ship will always have some climate impact. There is actually no alternative; if we want to understand processes and consequences of climate change, research has to be conducted in the Arctic. To gain a holistic perspective on the climate system, it furthermore takes inter-disciplinary collaboration, so you need a high-capacity, robust research platform that can support a large team operating in extremely remote locations for several weeks. The icebreaker Sir David Attenborough is optimally equipped for this task, and on this voyage we utilized the complete range of its capabilities on a mission to obtain valuable, highly special data.

How did you prepare for the expedition as a researcher?

I studied KANG-GLAC ahead of the expedition for research preparation, but my main mission is to collect my own samples and pursue my particular contributions to the project. The expedition is mainly about collecting samples of high relevance to one’s own research. I won’t be analyzing the samples and interpreting the findings until I get back to Bonn.

What sort of samples are you studying?

My research involves two types of samples: sediment (mud) and pore water (the water content of mud). The focus is on chemical changes that occur in sediments under specific conditions. Other scientists on board—we are a multidisciplinary team—are doing microscope analysis of the mud to find microfossils. Harmful impact from ongoing climate change is particularly great in the Arctic, which moreover is a region where we still have an inadequate understanding of many environmental processes. Those two circumstances in combination are why Arctic research is so important.

What is the process for taking samples?

We utilize different systems and methods to bring sediments from the ocean floor up onto the ship. One important thing in this process is to leave the deposit layers intact. The most recent layer of sediment is on the surface of the seabed, with older deposit layers beneath, forming a chronological record which we intend to preserve. Thus the typical process is to sink one or more pipes down to the seabed, which we then bore into the mud, as straight in as possible, using a weight. We then carefully retrieve the sediment-filled pipes up onto deck to collect samples. A range of different methods are used for sample taking. Often we cut the cores into slices, each slice taken as one sample. Being a relatively large team, we are able to assist each other in this work. It still takes several hours per station however, and we can only manage about three to four stations in a 12-hour shift.

Are you also involved in experiments of other researchers?

We take samples for other project partners as well, and are all highly specialized in our respective research fields. We all benefit from securing as many samples as possible, which we then study using as broad a range of methods as possible. All this within the framework of the overall project objectives. Thus through our own research each of us does our part in addressing the larger complex of issues.

What is the most important aspect of your research? Is there potential for something to go wrong?

To me it’s extremely important to take copious notes on the context from which the core samples are taken. We keep a logbook on every sediment core brought on board for recording the precise station coordinates and water depth among other information. Each individual sample is also labeled, designating the station and core depth. Core depth is determined in relation to the seabed surface as zero point of the depth scale. Amid all the busy, fast-paced work going on, mistakes can happen like mislabeling by mixing up two digits—but things like that are rapidly noticed and corrected. Much more frequently, problems arise during the actual drilling, which you may notice for example when the equipment comes back up on deck without any sediment. But even that is not a problem, we will just have another go at it!

Does your research concern the more recent sediment layers?

That’s right, we study very closely the later-forming sediment layers on top of the seafloor. These are often the most interesting deposits from a geochemical standpoint, as many processes take place in the upper 20 cm of seabed. But to reconstruct past environmental conditions you have to study much longer cores. The longer the core, the further back into the past you can peer, so we take some sediment cores up to 10 m in length in an effort to gain an understanding of past climatic changes.

Sampling

Bild © Universität Bonn / YouTube

What reference data do you use?

Referencing earlier published data from similar areas is always worthwhile, and this is standard procedure. Also, for expeditions of this kind, as much information as possible about the study area and any relevant particularities needs to be collected in advance. The basic fact is that we are moving in waters about which very little is known at this time, so first the ship always maps the seabed, looking out for sediments that could be suitable for drilling or taking other measurements. Based on the data collected, a decision may then be made on what analyses to carry out at specific stations. Each sample is unique, and thus valuable. The various different research objectives and methods this expedition involves are clearly characteristic of an initial data-gathering mission, to take its place alongside other Arctic studies.

How cold is the weather?

Upon our arrival in Greenland we’ve had a few days of freezing temperatures, but now it ranges from 3 to 8°C, so it’s become fairly warm. The wind can make it colder and, due to the humidity, even on cloudy days I sometimes feel cold. I work on deck most of the time, out in the open that means. That’s why I ensure that I protect myself properly against cold and wet conditions.

How do you protect yourselves against the cold and elements?

We wear several layers of clothing, always with something waterproof on the outside. For the current expedition I was actually provided with the appropriate clothes! On days that are very cold I first put on a synthetic piece of clothing, then something woolen, plus my waterproof workwear on top. However, when you work on a ship it’s often possible to step inside for a few minutes and warm yourself up.

How many personal items were you allowed to bring on board?

The ship I am on is very big, with a lot of space. That’s why no restrictions regarding the luggage were made beforehand. I like to travel light though and therefore packed as if I was going on a normal 2-week trip to somewhere cold. I can wash my clothes on the ship. I only brought along two books as I knew there would not be much spare time. There are board games and a couple of musical instruments here, but so far there’s hardly been time to play them.

What do you do in case of seasickness?

I have been very lucky and not been really seasick so far. Good advice for when there stronger waves at sea would be to ensure to always have some food in your tummy (simple biscuits are great) and look at the horizon. A lot of people become a bit sensitive towards caffeine when seasick. It often helps to skip the coffee and instead have a sparkling drink. If nothing else helps, there is always very good medicine against seasickness you can take!

Swell

Bild © Katrin Wagner

What do you when cabin fever hits you?

I try to find somewhere quiet and make it pretty obvious that I am not “open for a chat”, e.g. by reading a book. That works pretty well. Day-to-day, however, there’s not a lot of time for that. Then it’s important to remember to be patient and show empathy. Days and nights are long for everyone on board. Work is tiring and we’re all far away from our families and friends. It’s important not to take every comment to heart and allow everyone to also have a “bad day” from time to time. That approach works pretty well!

Do you have time to explore the surroundings?

Going for a walk on the ice or ashore is not possible for me, unfortunately. I work either on deck or in the labs on board. Trips out on the ice are dangerous and usually only taken when the projects requires to do so. Excursions ashore also pose a logistical challenge since we’re miles away from the next harbor. Greenland is the country of the polar bear, especially the east. It is not possible to go for a walk outside the few villages if you are not armed to protect yourself. We have a small boat on board, however, which we use to go out in waters less deep and take scientific measurements. I was able to go on a small trip with this boat (Erebus) and much enjoyed that! Taking a small trip to the glacier at sunset and watching our current “home” (the RRS Sir David Attenborough polar research vessel) from afar was spectacular!

What is the worst thing for you on board the ship, and what is the best?

There are a lot of things I love about expeditions like this. At the top of my list is the camaraderie between the scientists and the crew. We see ourselves as one single team, and even though we usually didn’t know each other before the voyage, we are there for each other with help and advice most of the time, even for minor problems. To me it is also an incredible privilege to experience the breathtaking landscape. I have worked in the Arctic for several years now, but I am always touched and astounded by the supreme beauty of the ice in this place of solitude. One negative point is having very little time and hardly any place to get in some me-time alone. I like to retreat and be alone with my thoughts for a while at times, but often that’s just not possible here.

How is the ship supplied?

That depends on the duration of the expedition, and on the destination. It's a six-week voyage to a very remote location where it’s not easy to restock supplies. The Sir David Attenborough is a big ship however with plenty of storage space for food and fresh water, so we don’t need to stop for supplies. Fresh vegetables and fruit may start to run out though at some point, this being a six-week trip. Thank god for canned goods and freezers!

The food on board is very good in general, leaving little to be desired. We get three hot meals a day, often with dessert. And me and my night-shift colleagues get another hot meal prepared around midnight for our “lunch”. It’s hard work studying sediments from the sea floor, and I often get wet and cold. Sometimes by the end of the shift you could really use a few extra calories and some feel-good food. So I bought a few chocolate bars before we embarked which I keep in a drawer in my cabin “for emergencies”. You never know when you might need one.

What are your accommodations like on the ship?

My cabin on the ship is very comfortable, which has the typical bunk beds, like most ship cabins. My cabin mate is an associate on the Sediment team. We even have a small sofa, and a desk! It's sort of like living in a caravan. Everything is quite small, but the space is efficiently used, so it feels quite cozy!

How are the first few days on board?

The first few days are usually spent getting to know the ship, the crew and the science team. We were given a ship tour right when we arrived, which was definitely the right idea, as the vessel is huge, with nine decks; and there are numerous doors and rooms you are not allowed to enter. We did have a round of introductions and an on-deck barbecue was held within the first few days on our way up to Greenland as an opportunity to get to know the ship’s crew better. Our cook conducted a pub quiz afterwards, which we all enjoyed.

What is your daily routine like?

Everything was quite relaxed for the first few days of the voyage from our home port in Scotland. The main agenda item for everyone on the way up to Greenland was organizing and preparing one’s own work. In the evenings there was plenty of time for socializing, doing crossword and jigsaw puzzles. We have since transitioned over to “normal” scientific operations, which for me and my team means working a night shift. So I get up at 7 pm, have breakfast and then go up on deck, where we take sediment cores and samples. The work is tremendous fun, we always get wet and dirty, and have to be careful not to get too cold. We enjoy the Arctic sunset while waiting for the sediment cores to be drawn up out of the water, and then about an hour later we enjoy the sunrise! Those are truly magical moments! My shift ends at 8 am, when the daytime teams take over. There is some leisure time, for books, music, movies, etc., but usually I go to bed pretty soon after work—exhausted but happy.

Arctic expedition

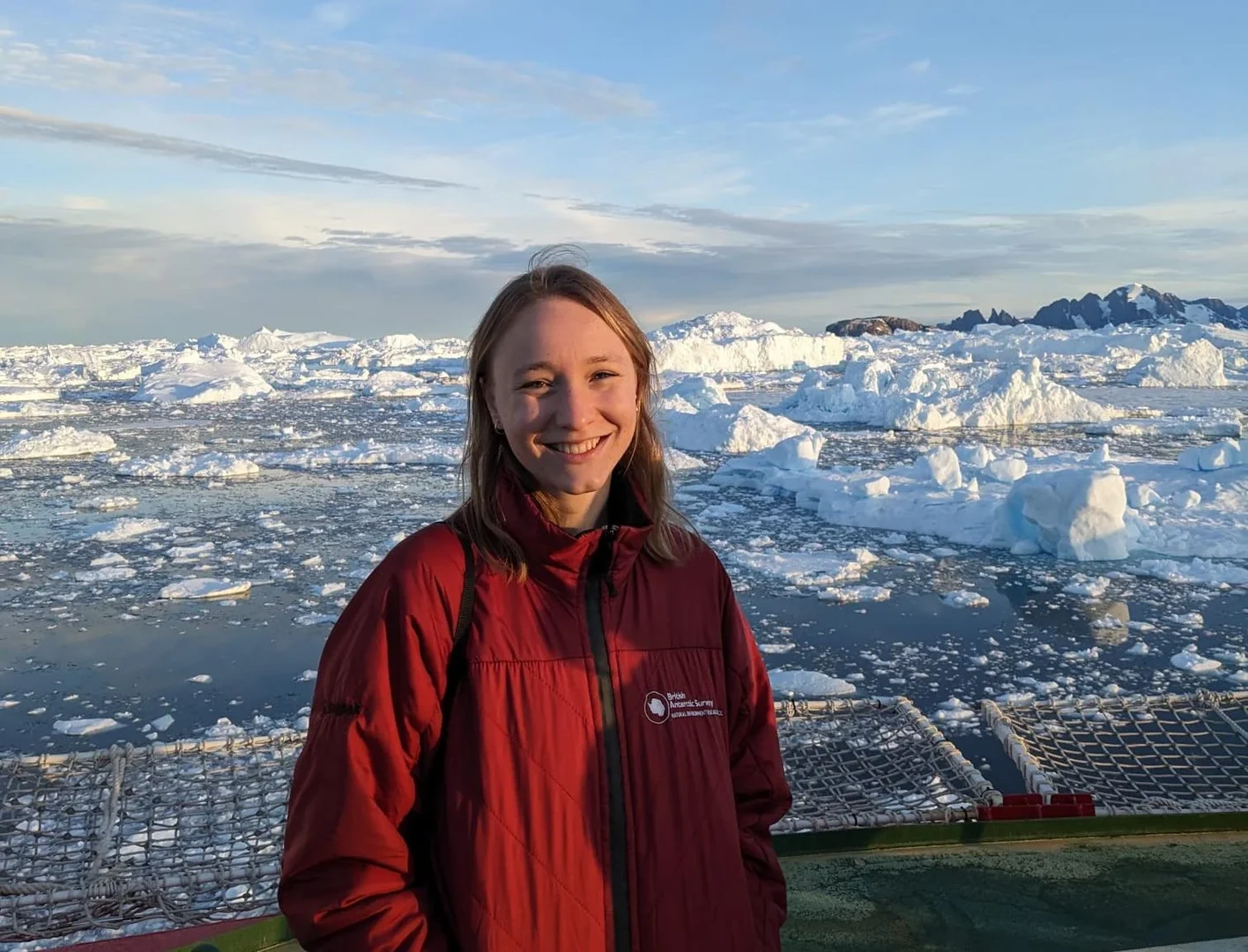

What chemical processes occur in the oceans, and how are these changing as the climate becomes warmer? This is the question being addressed by the Environmental Geology working group at the University of Bonn Institute of Geosciences, headed by Professor Christian März. Research is being conducted in the field as well as in the lab, up in the Arctic region of southeast Greenland. Doctoral student Katrin Wagner, as part of an interdisciplinary team of 40 researchers and staff from world-leading research institutes, is embarking on a six-week expedition on the research icebreaker RRS Sir David Attenborough to study evidence of glacial change in Greenland and sea life in the coastal waters of the earth’s largest island. Her role in this mission, called the KANG-GLAC project, is to extract sediment cores from the seabed and take samples for subsequent analysis in a University of Bonn lab. “The samples taken will allow us to identify the geochemical processes currently taking place in the seabed, so we will learn a lot about how glacial activity is affecting conditions in the marine environment. We will also be collecting evidence of how these conditions may have changed over time,” Wagner explains.

Living and working on a research vessel

If you have always wanted to know what it is like to work on board a research vessel, you will now have a great opportunity to find out from first-hand reports. During the expedition, doctoral student Katrin Wagner is taking questions from interested members of the public, posting answers on the University’s Instagram account (@universitaetbonn)1 and the University website. You can send in your questions by email to wissenschaftskommunikation@uni-bonn.de.

The Greenland Ice Sheet is decaying at an accelerating rate in response to climate change. Warm Atlantic waters moving through fjords eventually meet the ice fronts of marine-terminating glaciers, increasing melting and causing icebergs to break off. In turn, the injection of increased fresh meltwater into the ocean is altering both ocean currents and marine ecosystems around Greenland and farther afield in the North Atlantic, with potential effects on UK weather systems.

The KANG-GLAC project aims to determine the intricate processes driving these changes by studying what is happening now and during warm climatic periods in the past. Researchers can help anticipate future ice-ocean-marine ecosystem changes by extending the modern observational record back through the last 11,700 years, a period known as the Holocene. This includes a time when summer temperatures in Greenland were 3-5°C warmer than today: the Holocene Thermal Maximum. While some records of 20th-century iceberg calving and warm water inflows exist around Greenland, records of how glaciers then decay and the effects on marine productivity over many decades to millennia are lacking. Dr Kelly Hogan, a marine geophysicist from British Antarctic Survey is Co-lead on the project. She says: “Our expedition is extremely timely as we are seeing every day in the news how the Arctic is changing, and we know there will be knock-on effects for the rest of the planet. We need to understand how the Greenland Ice Sheet is likely to decay over the coming decades to centuries, and what the subsequent effects will be on both ocean currents and marine food webs. This is now urgent information for us to gather so policymakers can understand what will happen in the North Atlantic and set out appropriate adaptation and mitigation plans.”

This three-and-a-half year project will generate records of glacier, ocean, and ecosystem change for the Holocene era at key sites close to Kangerlussuaq Fjord in SE Greenland. The team includes a mix of researchers – including oceanographers, biologists and geologists – who will collectively use a range of instruments to retrieve samples from rocks on land, from the ocean, and from the seafloor to gain a comprehensive picture of this region and its current and potential future response to environmental change.

Using state-of-the-art capabilities of the RRS Sir David Attenborough and deploying advanced underwater robotics such as the Gavia, operated by the Scottish Association for Marine Science (SAMS), the team will investigate modern interactions between meltwater expelled from glaciers and the inflowing warm ocean waters, as well as how this affects primary productivity in Greenland’s fjords and coastal seas.

In parallel, marine sediment cores from the seafloor and terrestrial rock samples collected using helicopters deployed from the ship will reveal changes in glacier size, ocean temperatures, and carbon storage at the seafloor all changed during the Holocene. Professor Colm O’Cofaigh, a glacial and marine geologist from the Department of Geography, Durham University, is Co-Lead PI on the project. He says: “Understanding the Holocene record of Greenland Ice Sheet change and the role of the ocean thereon is crucial for placing current observations of ice and ocean change into their longer-term context and for underpinning predictions of future change. The range of tools to be deployed from the RRS Sir David Attenborough during the KANG-GLAC cruise provides an unprecedented opportunity to assess this change over the last 11,700 years.”

KANG-GLAC: the race to understand Greenland's melting glaciers | British Antarctic Survey

Bild © British Antarctic Survey / YouTube