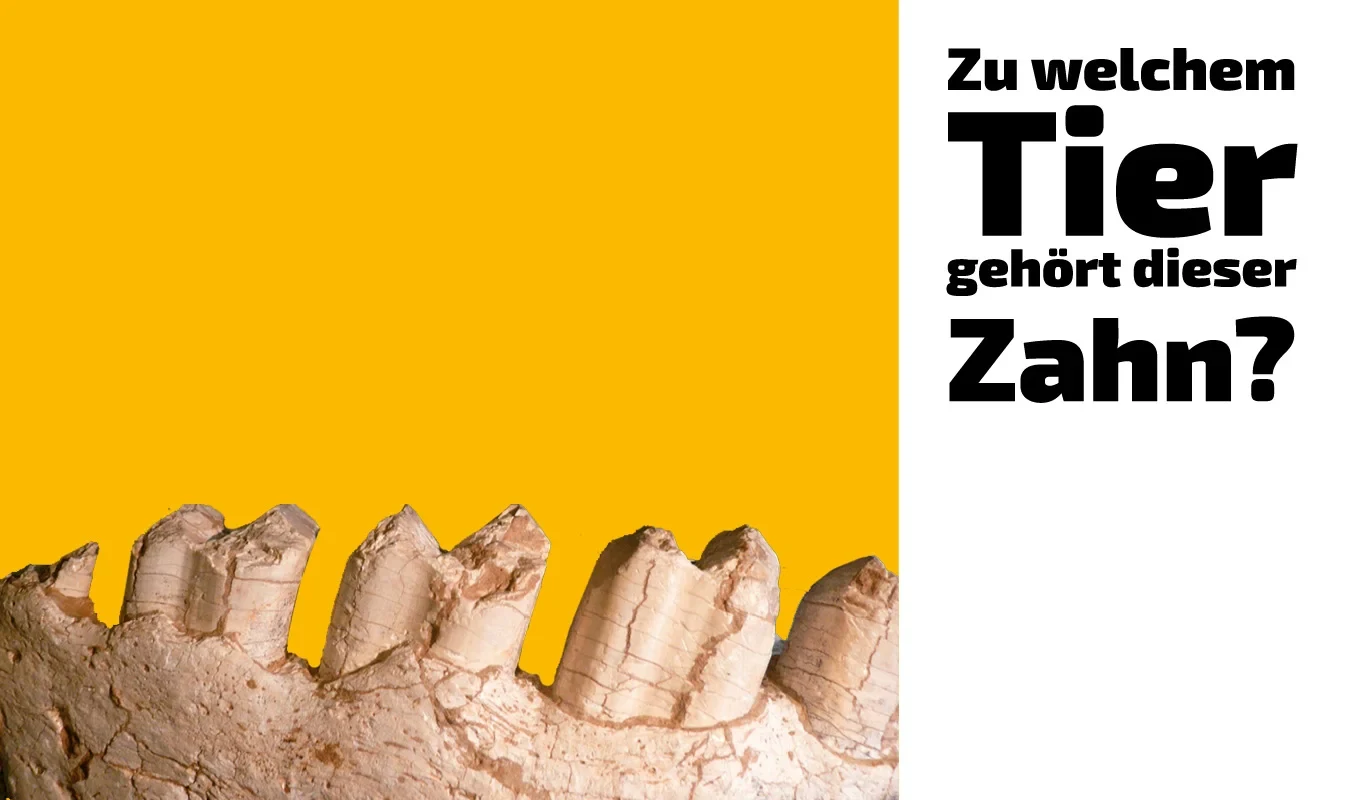

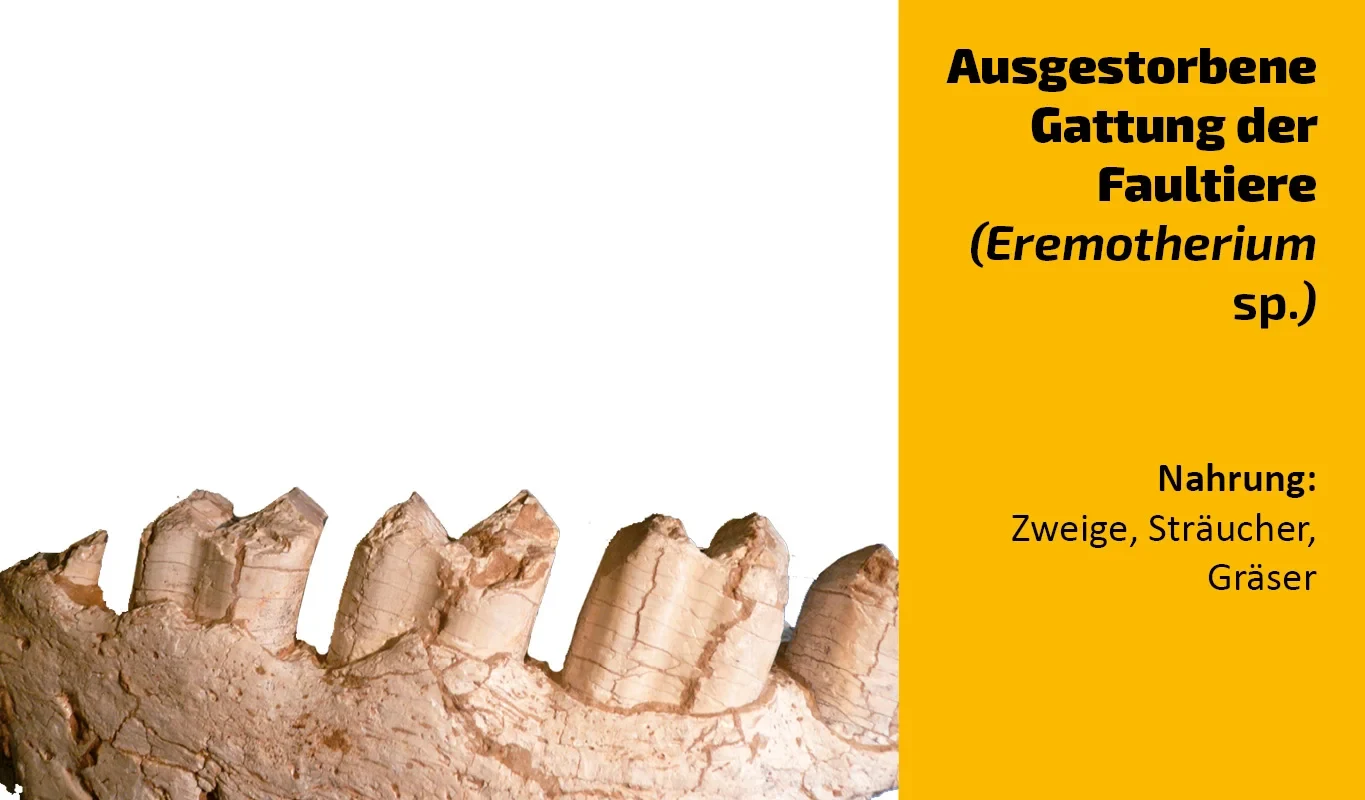

Often a mere few millimeters in size, they nevertheless carry a wealth of information about the sunken worlds of long-extinct animals. “Teeth reflect how mammals interacted with their environment,” says paleontologist Prof. Dr. Thomas Martin, who has published a book, Mammalian Teeth, together with his retired colleague Prof. Dr. Wighart von Koenigswald.

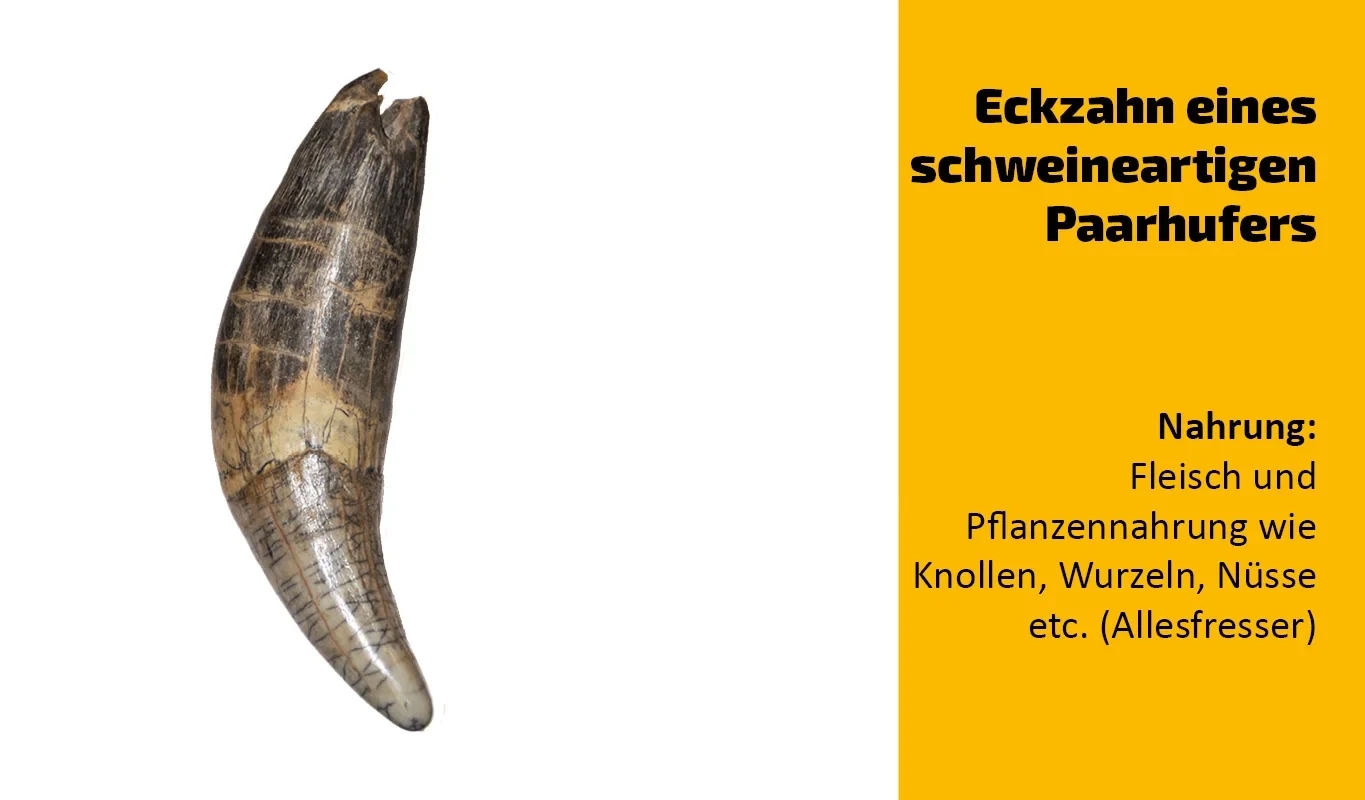

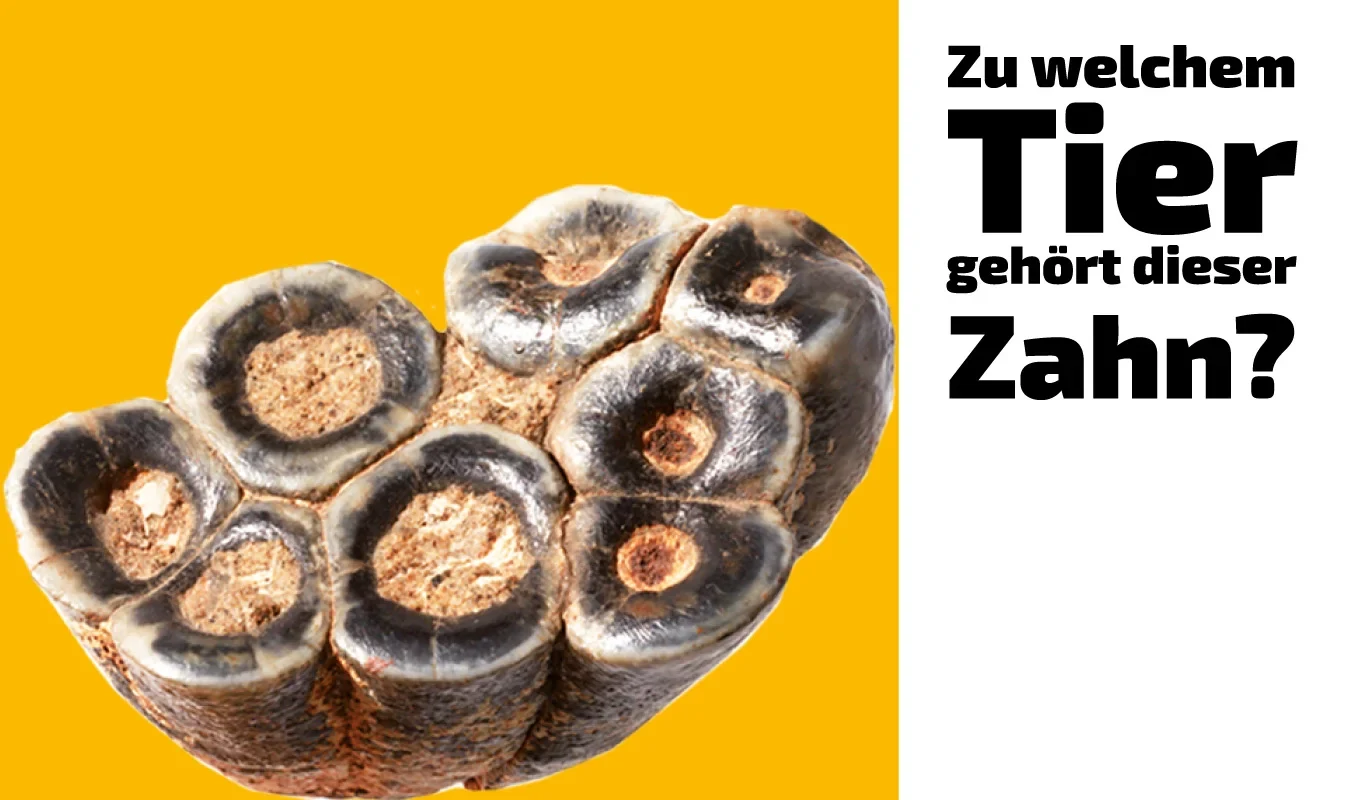

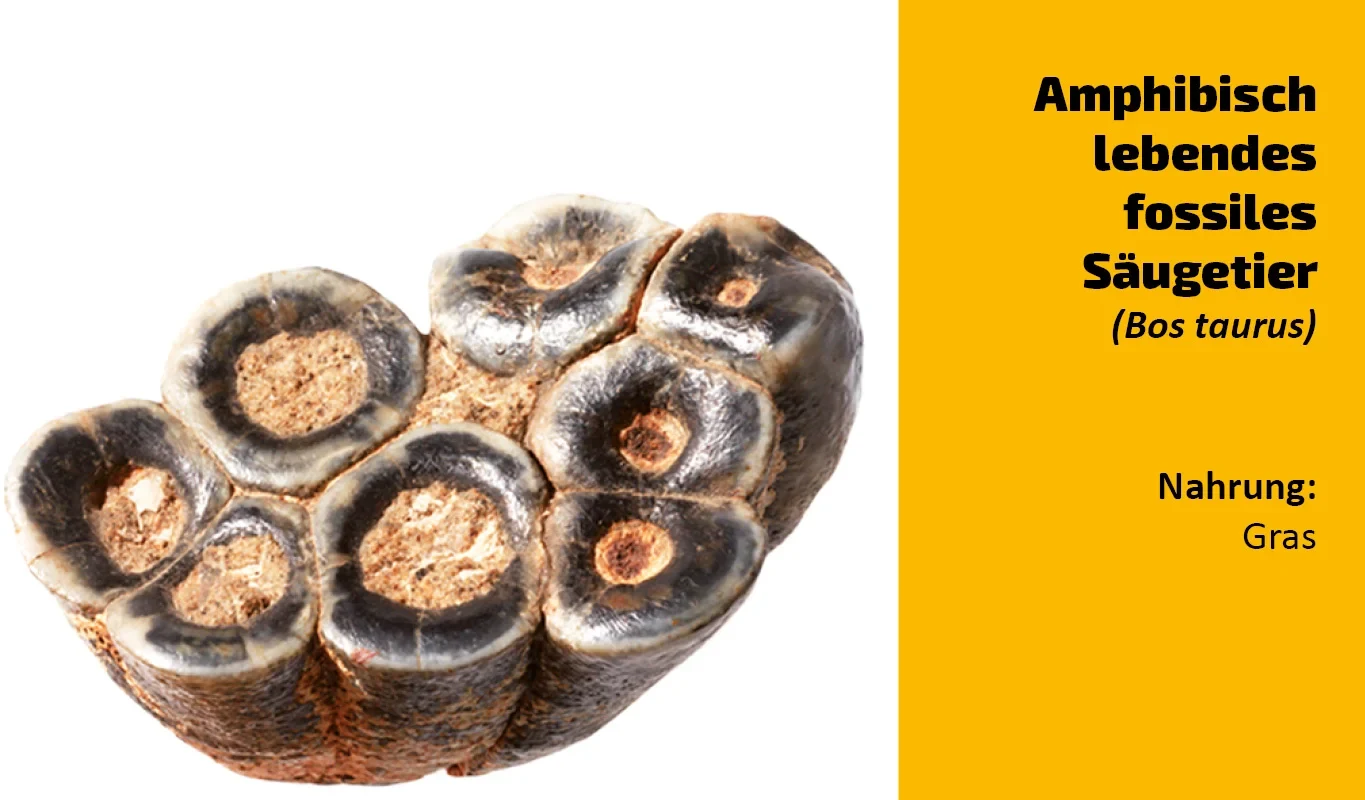

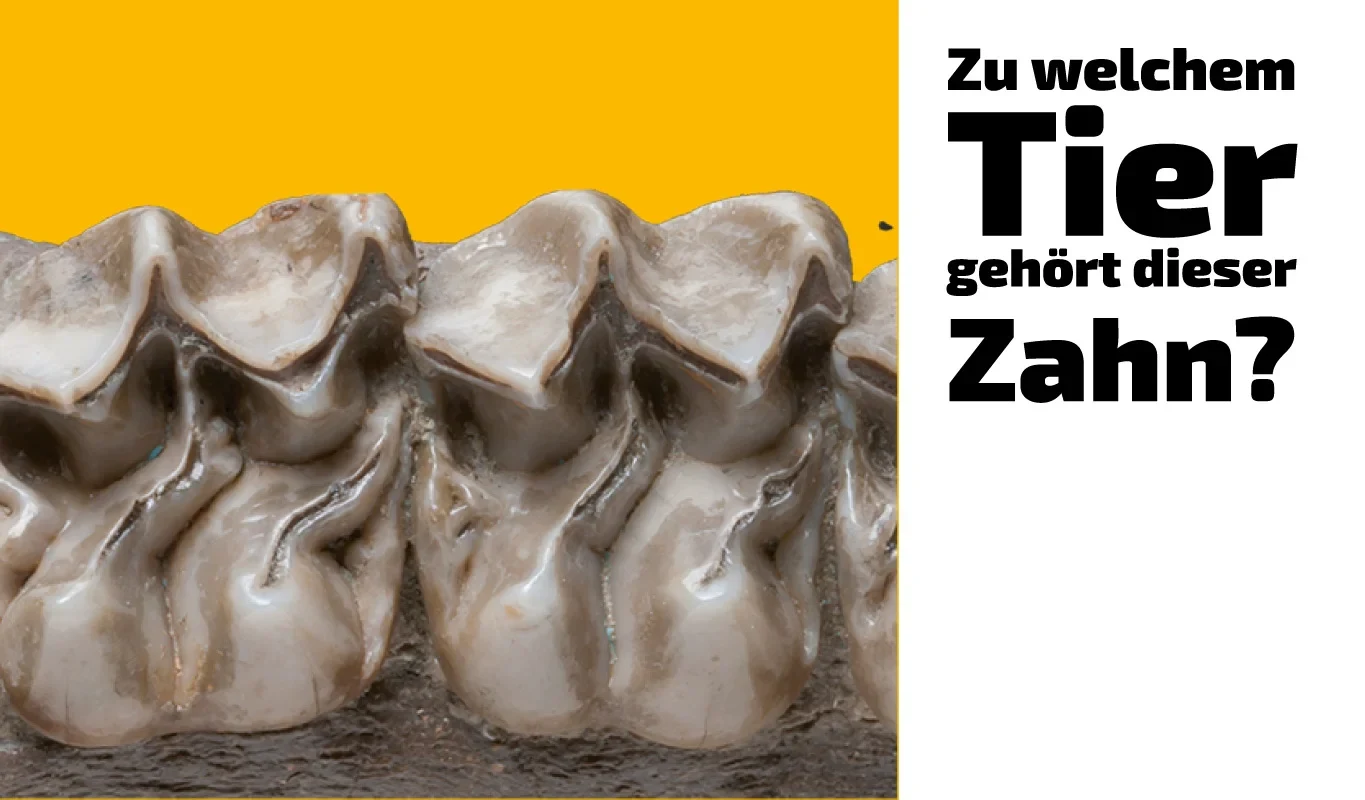

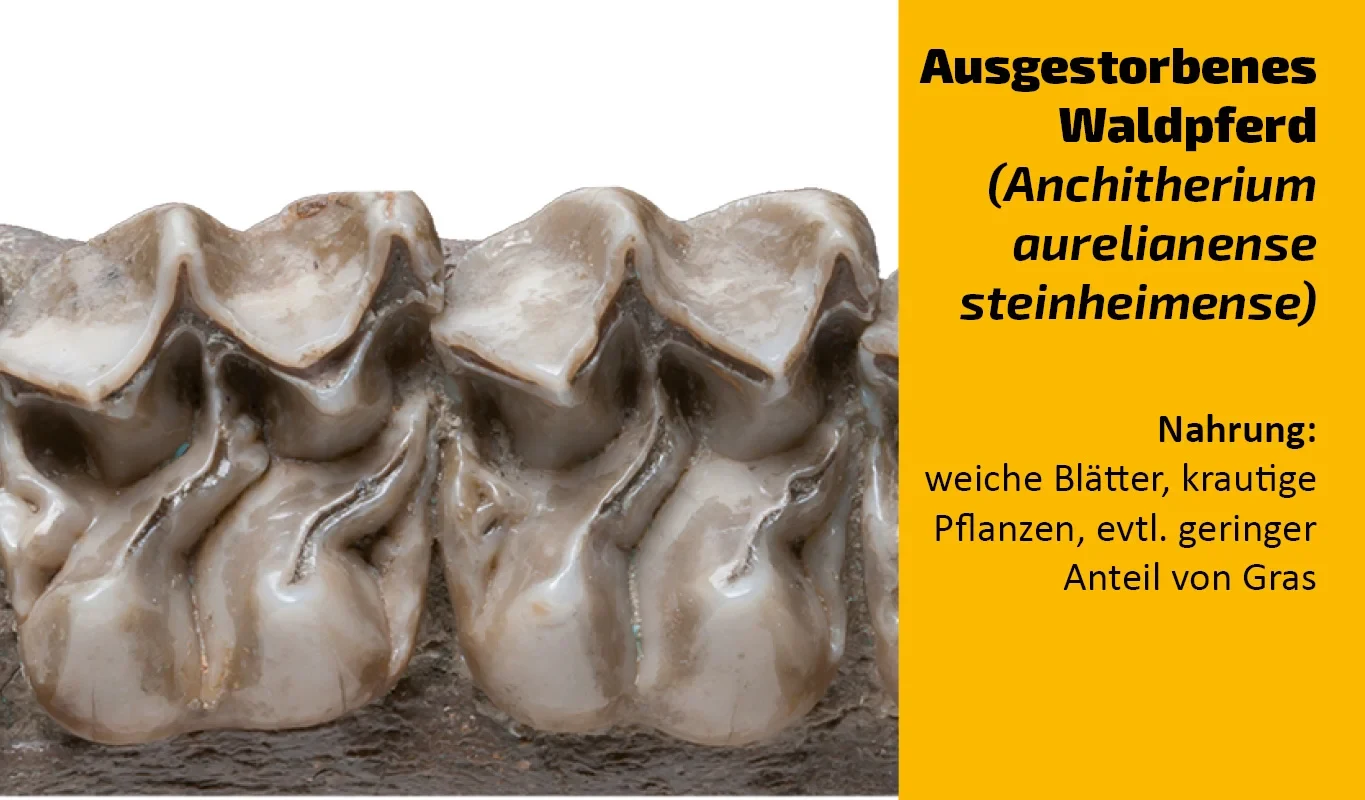

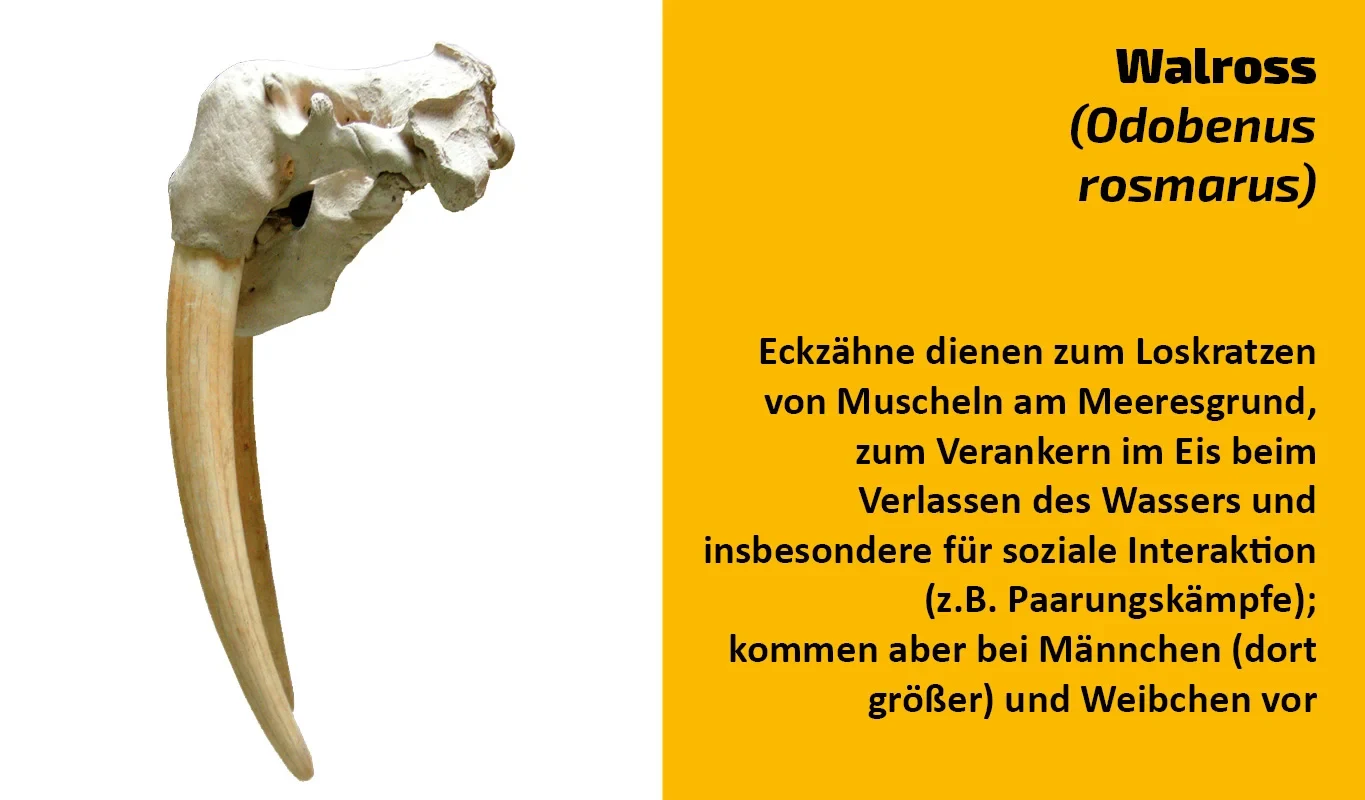

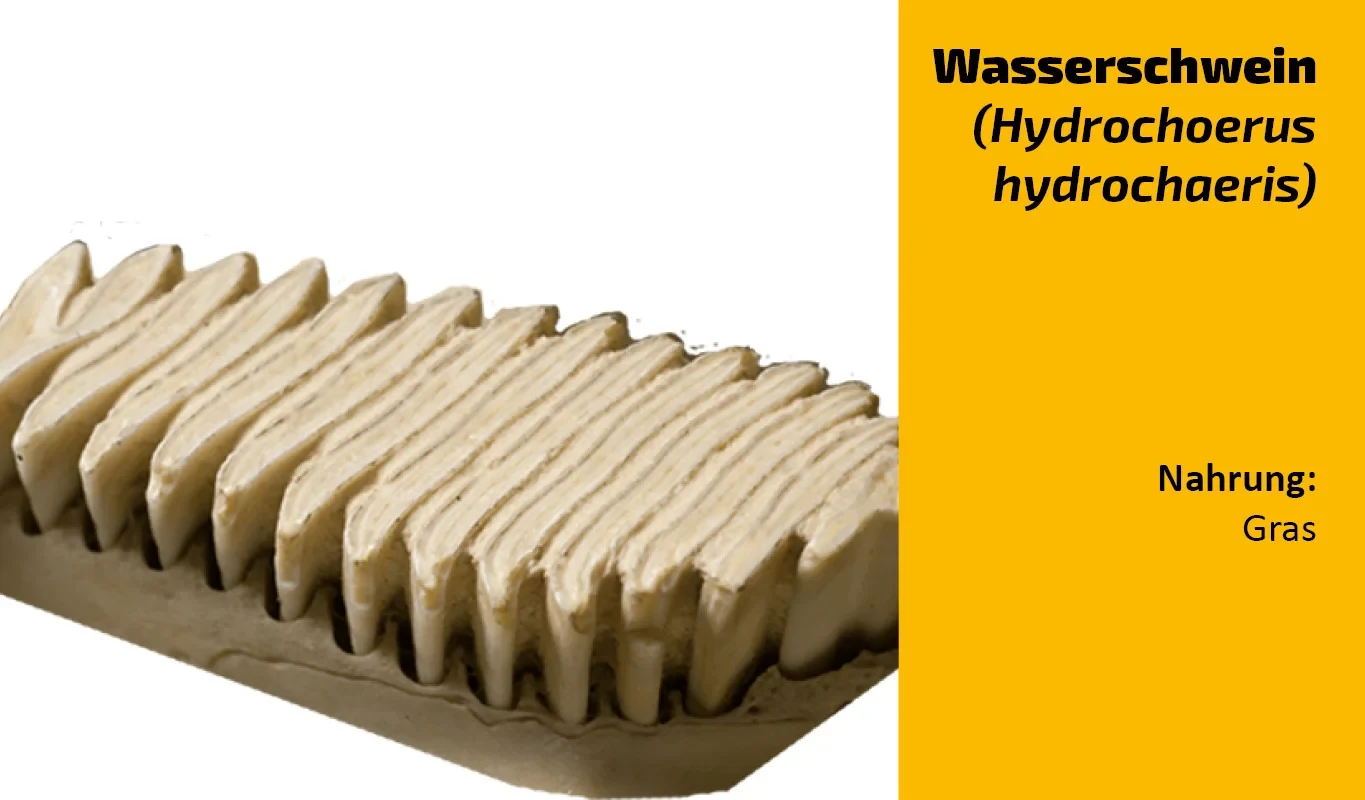

The shape of teeth and traces of their chewing action can be used to indicate whether a mammal fed on tough grass or soft leaves, how it ground up its food and how much energy it obtained in the process. In an ideal scenario, therefore, a few teeth will suffice to hypothesize what the animal’s environment might have looked like.

This is all possible thanks to cutting-edge methods such as computed microtomography, which allows the teeth to effectively be X-rayed. High-resolution surface analysis and three-dimensional imaging have also helped enable major progress to be made in this field.

In 2008, a research group entitled “Function and Performance Enhancement in the Mammalian Dentition – Phylogenetic and Ontogenetic Impact on the Masticatory Apparatus,” which has been funded by the German Research Foundation, began to study teeth from mammalian fossils and compare them with those of animals still alive today. Besides the University of Bonn, the project also involved the Senckenberg Research Institute and Natural History Museum Frankfurt, the Zoological Museum at the University of Hamburg and the Swedish Museum of Natural History in Stockholm. Scientists and researchers working in fields ranging from paleontology, zoology and anthropology through to animal nutrition and biomechanics contributed their expertise.

Finding and extracting evidence in the remotest corners of the Earth is laborious work: the paleontologists sometimes use sieves to pan river sediment for fossilized teeth, like gold prospectors.