The term glomerulonephritis denotes several types of chronic kidneys inflammation that can lead to the loss of renal function. Most of these conditions are due to autoaggressive immune responses that damage the kidney tissue. Although glomerulonephritis can be treated with immunosuppressive drugs such as corticosteroids, sometimes there is no way of stopping the self-destructive immune response. This may lead to a complete loss of renal function, necessitating continuous dialysis or a kidney transplant.

Researchers led by Professor Jan-Eric Turner from the Center for Internal Medicine at the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf and by Professor Christian Kurts from the Institute of Molecular Medicine and Experimental Immunology at the University Hospital Bonn, who is a member of the ImmunoSensation2 Cluster of Excellence and the Life & Health Transdisciplinary Research Area at the University of Bonn, have now found that certain vitamin metabolites can support the treatment of these conditions.

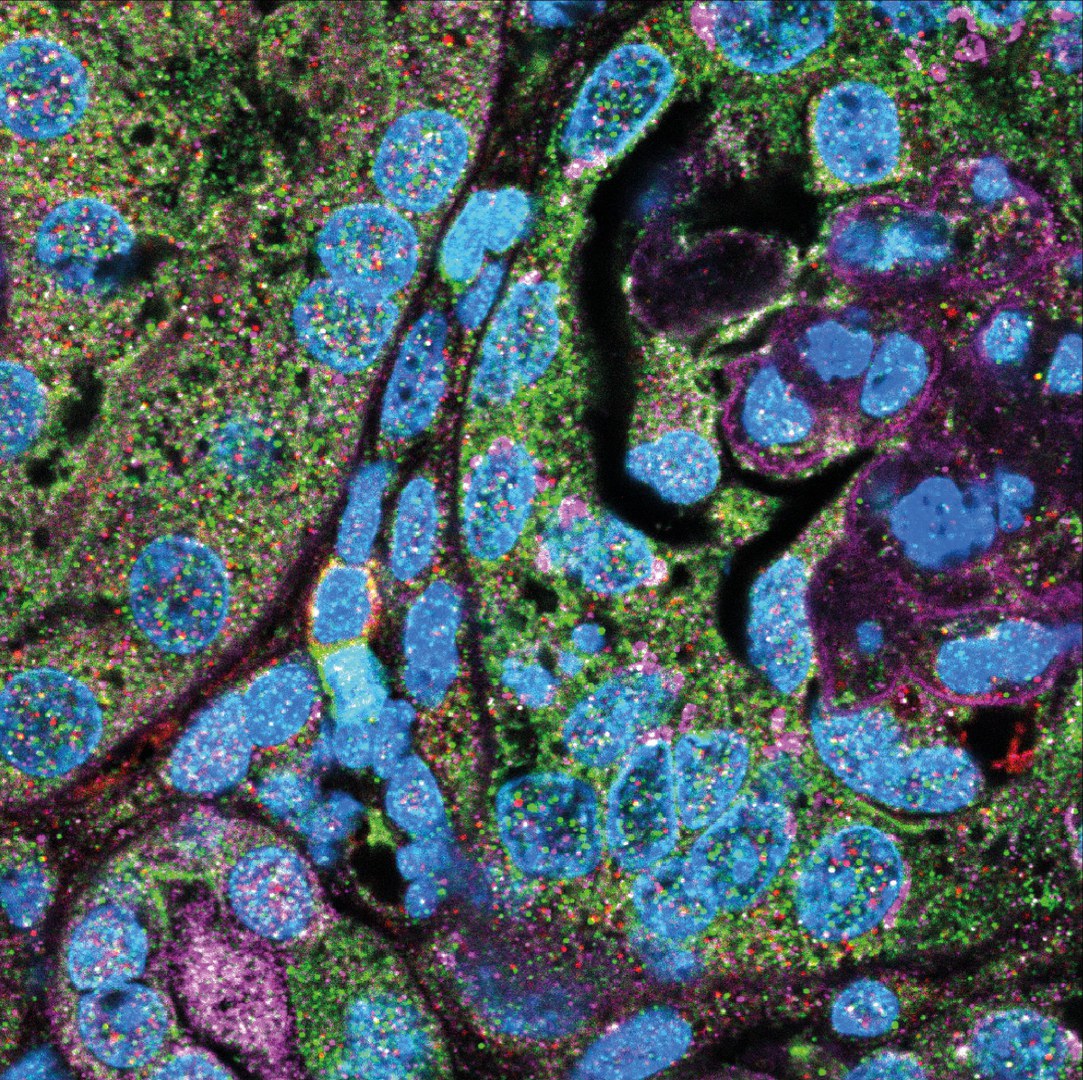

The researchers were the first to observe so called mucosal-associated invariant T cells (MAIT cells) ins both healthy and inflamed human kidneys. These rare immune cells are normally found in mucosal tissue such as in the intestine or lungs, where they perform sentinel functions against infections. “They are activated by metabolites of vitamins B2 and B9, which many infectious bacteria produce, and trigger defense responses as a result,” Professor Kurts says.

MAIT cells protecting the kidney

“In kidneys of glomerulonephritis patients and of mice with models of such diseases, these rare immune cells were activated by the resident kidneys immune cells —known as mononuclear phagocytes— that produce molecules that attracted the MAIT cells,” Professor Turner explains. Mice that lacked MAIT cells or in which mononuclear phagocytes could not attract MAIT cells experienced a more severe progression of their glomerulonephritis. Conversely, some of the mice that possessed more MAIT cells were protected.

These findings suggested that MAIT cells play a protective role in the kidney. In a therapeutic trial, the researchers treated mice suffering from glomerulonephritis with an artificial vitamin B2 metabolite that matched their natural ligand, and this alleviated the disease progression.

“The protective effect was not strong enough to prevent the experimental glomerulonephritis entirely,” Professor Kurts concedes. However, the researchers believe that it could be used to supplement existing therapies and make them more effective or to reduce the dose of glucocorticoids required in treatment. “More research and clinical trials will be needed before this becomes a viable option in therapy,” Professor Turner points out.