The African cichlid Pelvicachromis taeniatus certainly boasts magnificent coloration: In the females, a purple belly and a blue-green shimmering side stripe signal the onset of sexual maturity. The males however garner attention from potential sexual partners with bright orange and yellow shades. The striking coloration (evolutionary biologists also speak of “ornaments”) has a significant disadvantage: It also catches the eye of potential predators. Biologists of the research group of Prof. Dr. Theo C.M. Bakker at the Institute of Evolutionary Biology and Animal Ecology at the University of Bonn have therefore investigated how the presence of predators affects the appearance of the fish.

To do so, they raised two groups of fish and observed them over a two-year period. In one of the two groups, they regularly added an extract obtained from conspecifics to the water. “When cichlids fall prey to a predator, alarm substances are released”, explains Dr. Denis Meuthen, who has since moved to the University of Saskatchewan in Canada. “These alert other members of the same species of the imminent danger. The fish extract we used also contained such alarm substances.”

Body size and paleness as life insurance

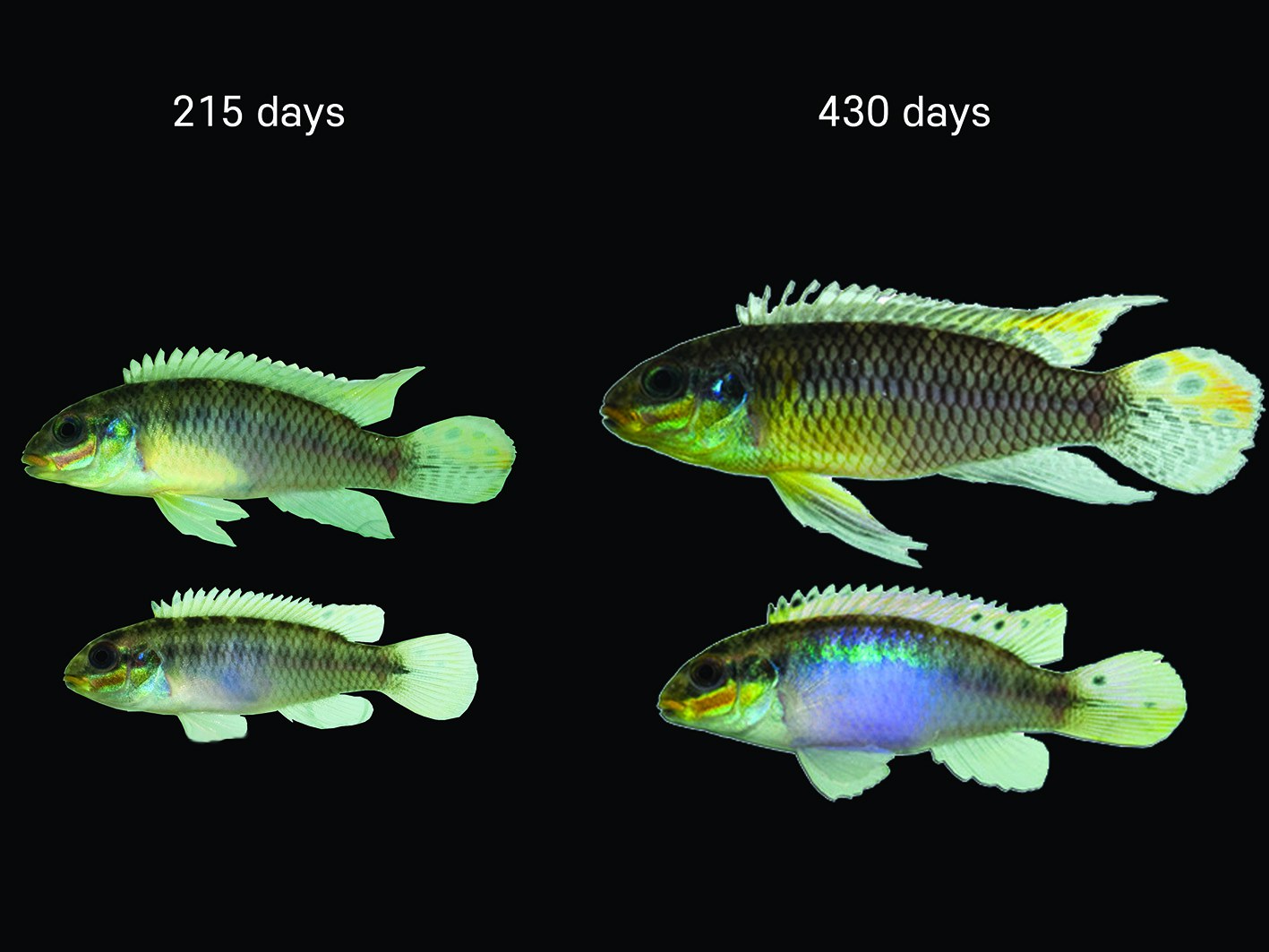

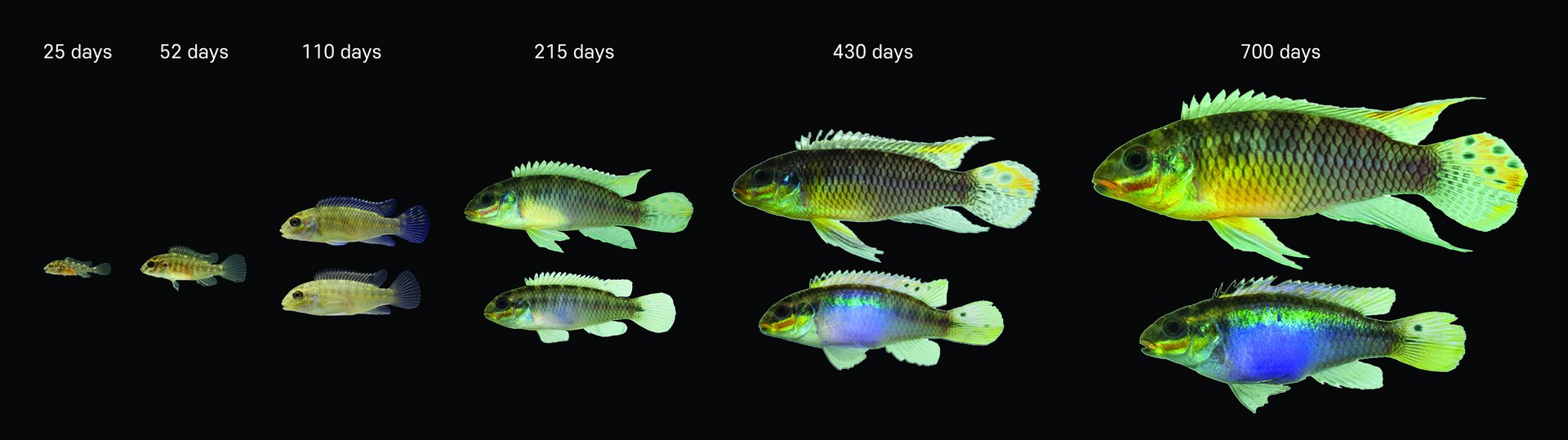

In all other aspects, the fish were kept under identical conditions. The researchers then took photographs of the cichlids at six different times during development and compared these with each other. The images revealed some differences between the two groups: The males grew faster in the supposed presence of predators. They also developed larger eyes and the spines of their dorsal fins were longer.

“We assume that the animals reduce their risk of ending up as a predator’s meal this way”, explains Dr. Timo Thünken. “Predatory fish have more difficulty catching larger prey with spiny fins and have problems swallowing them. Additionally, large eyes may help detect predators faster.”

There was also another discovery: At the beginning of their sexual maturity, the males were more discreetly colored than their counterparts from the tank without alarm signals. This too was probably an adaptation to the supposedly increased risk of being eaten.

Surprisingly however, the differences were only present in males. The reason for this may be a consequence of the way of life of this cichlid species: The females deposit their eggs in breeding caves and care for them intensively. The males on the other hand tend to stay outside the caves and defend the surrounding area against rivals and egg predators. “They are therefore far more exposed and more likely to fall prey to an enemy”, explains Thünken.

However, courtship coloration development was delayed in males. At approximately one year age, the animals from both groups had the same conspicuous color. “The ornaments are important social signals”, explains Meuthen. “Towards one’s own sex, conspicuous coloration is a signal of dominance. At the same time it attracts females looking for a mate.” In other words: Less conspicuous males may live longer - but they often stay single.

The study was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG).

Publication: D. Meuthen, S. A. Baldauf, T. C. M. Bakker, and T. Thünken: Neglected patterns of variation in phenotypic plasticity: Age- and sex-specific antipredator plasticity in a cichlid fish. The American Naturalist, DOI: 10.1086/696264

Contact:

Dr. Denis Meuthen

Department of Biology

University of Saskatchewan, Canada

E-mail: denis.meuthen@usask.ca

Dr. Timo Thünken

Institute of Evolutionary Biology and Animal Ecology

University of Bonn

Tel.: +49 (0)228/735114

E-mail: tthuenken@evolution.uni-bonn.de