Plastics are usually made from petroleum, with the associated impacts in terms of fossil fuel depletion but also climate change: The carbon embodied in fossil resources is suddenly released to the atmosphere by degradation or burning, hence contributing to global warming. This corresponds to about 400 million metric tonnes of CO2 per year worldwide, almost half of the total greenhouse gases that Germany emitted to the atmosphere in 2017. It is estimated that by 2050, plastics could already be responsible for 15% of the global CO2 emissions.

Bioplastics, on the other hand, are in principle climate-neutral since they are based on renewable raw materials such as maize, wheat or sugar cane. These plants get the CO2 that they need from the air through their leaves. Producing bioplastics therefore consumes CO2, which compensates for the amount that is later released at end-of-life. Overall, their net greenhouse gas balance is assumed to be zero. Bioplastics are thus often consumed as an environmentally friendly alternative.

But at least with the current level of technology, this issue is probably not as clear as often assumed. “The production of bioplastics in large amounts would change land use globally,” explains Dr. Neus Escobar from the Institute of Food and Resource Economics at the University of Bonn. “This could potentially lead to an increase in the conversion of forest areas to arable land. However, forests absorb considerably more CO2 than maize or sugar cane annually, if only because of their larger biomass.” Experience with biofuels has shown that this effect is not a theoretical speculation. The increasing demand for the “green” energy sources has brought massive deforestation to some countries across the tropics.

Dr. Neus Escobar and her colleagues Salwa Haddad, Prof. Dr. Jan Börner and Dr. Wolfgang Britz have simulated the effects of an increased demand for bioplastics in major producing countries. They used and extended a computer model that had already been used to calculate the impacts of biofuel policies. It is based on a database that depicts the entire world economy.

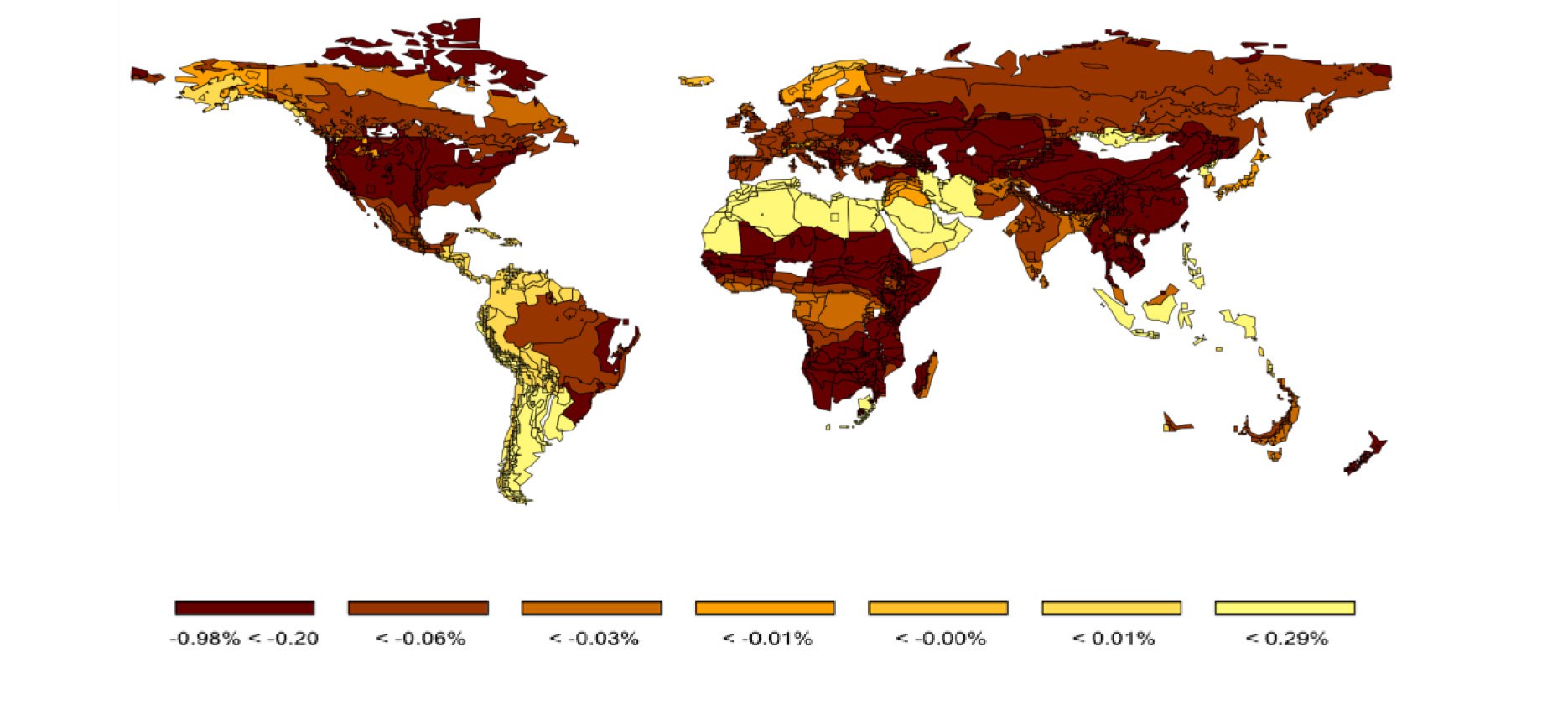

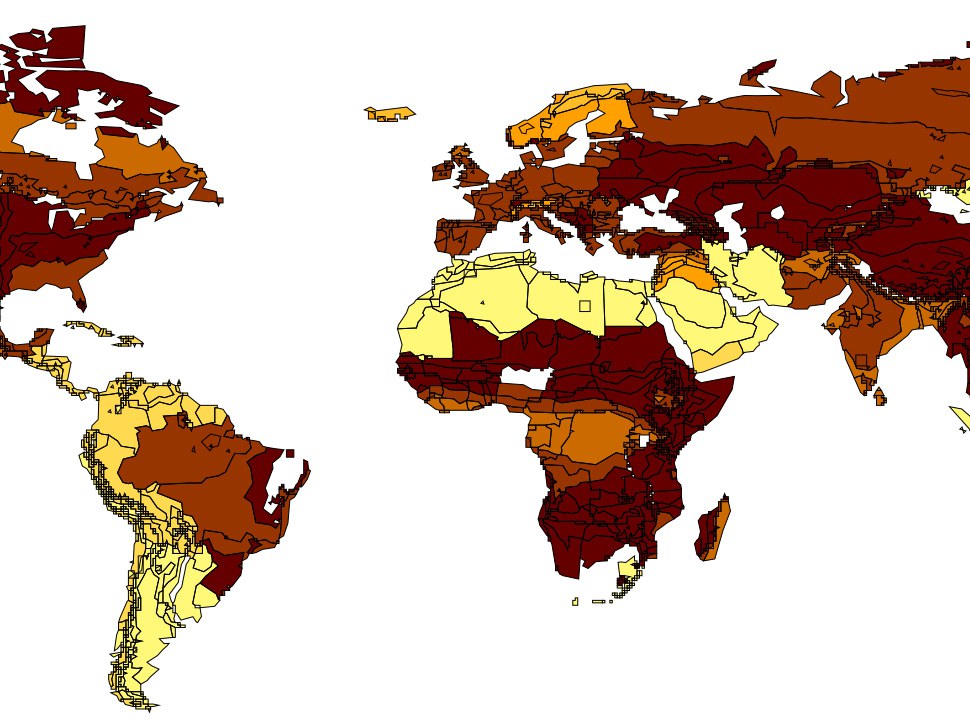

“For our experiment, we assume that the share of bioplastics relative to total plastic consumption increases to 5% in Europe, China, Brazil and the USA,” she explains. “We run two different scenarios: a tax on conventional plastics compared with a subsidy on bioplastics.” The most dramatic effects are found for the tax scenario: As fossil-based plastics consequently become considerably more expensive, the demand for them falls significantly. Worldwide, 0.08% fewer greenhouse gases would be released each year. However, part of this decline is due to economic distortions, as the tax also slows economic growth.

More fields, fewer forests

At the same time, the area of land used for agriculture increases in the tax scenario, while the forest area decreases by 0.17%. This translates into enormous quantities of CO2 being emitted into the atmosphere. “This is considered to occur as a one-time effect,” Escobar explains. “Nevertheless, according to our calculations, it will take more than 20 years for it to be offset by the savings achieved by fossil substitution.”

All in all, it takes a lot of time for the switch to bioplastics to pay off. Furthermore, the researchers estimate the societal costs of this policy to decrease one tonne of CO2 at more than 2,000 US dollars - a high sum as compared to biofuel mandates. A subsidy to bioplastics would have very different effects on the global economy. However, both the compensation period and the costs for climate change mitigation would remain almost the same as with the tax.

“Consuming bioplastics from food crops in greater amounts does not seem to be an effective strategy to protect the climate,” said the scientist. Especially because this would trigger many other negative effects, such as rising food prices. “But this would probably look different if other biomass resources were used for production, such as crop residues,” says Escobar. “We recommend concentrating research efforts on these advanced bioplastics and bring them to market.”

The belief that bioplastics will reduce the amount of waste in the oceans may not even come true. Just because plastics are made from plants does not automatically make them easily degradable in marine environments, Escobar emphasizes. “Bio-PE and Bio-PET are for example not biodegradable, same as their petroleum-based counterparts.” Bioplastics and biomaterials have however one clear advantage: They help to reduce the fossil fuel dependency of highly industrialized regions. The scientists conclude that if governments really want to protect the environment, they should rather pursue a different strategy: It makes more sense to use plastic sparingly and to ensure that it is actually recycled.

Publication: Neus Escobar, Salwa Haddad, Jan Börner and Wolfgang Britz: Land use mediated GHG emissions and spillovers from increased consumption of bioplastics; Environmental Research Letters; https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aaeafb

Contact:

Dr. Neus Escobar

Institute for Food and Resource Economics

University of Bonn

Tel. +49 (0)228/733776

E-mail: neus.escobar@ilr.uni-bonn.de