Creating immersive explorable spaces

“Most of our students have never experienced something like this before,” says the head of the project Dr. Matthias Lang. “If you’re studying archaeology or Egyptology it’s often just not possible to travel to Egypt or Italy to visit monuments or buildings on location, let alone explore, experience and compare tombs.” It’s a problem that Lang would like to solve. He recently returned to Bonn after a period at the University of Tübingen.

While at Tübingen, he used laser scanning techniques, photography and computers to make parts of the Saqqara necropolis digitally accessible. The project was influenced by his own experience of studying ancient civilizations: “I studied classical archaeology in Bonn. As someone new to the field I could never really imagine what a temple or burial ground looked like just from studying plans and photos,” says Lang.

He’s convinced of the value of digital documentation. “The advantage is that digital technology provides beginning students with access to places that would otherwise be inaccessible or hard to reach, making these locations more vivid and more tangible, which in turn helps students to improve their spatial perception skills.” The project at the Bonn Center for Digital Humanities (BCDH) aims to use virtual reality to take digital collaborative teaching to the next level. Sarcophaguses and tombs, excavation sites, Roman ruins and early Christian churches can thus be accessed virtually from any desk or lecture theatre. The project is a sub-cluster of the virtual collaboration project ViCO and links the subjects of Egyptology, Christian archaeology, classical archaeology, ancient American studies / ethnology and art history.

First projects with VR processing

Working with the teams led by Prof. Dr. Martin Bentz and Prof. Dr. Sabine Feist, Matthias Lang is currently planning the first projects in Bonn to use virtual processing. These include the crypt of St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice and the Etruscan necropolis of Cerveteri, north of Rome. In the fall of 2021, a team from BCDH began the on-site digital documentation of the study sites. Projects involving other archaeological objects are planned for the future.

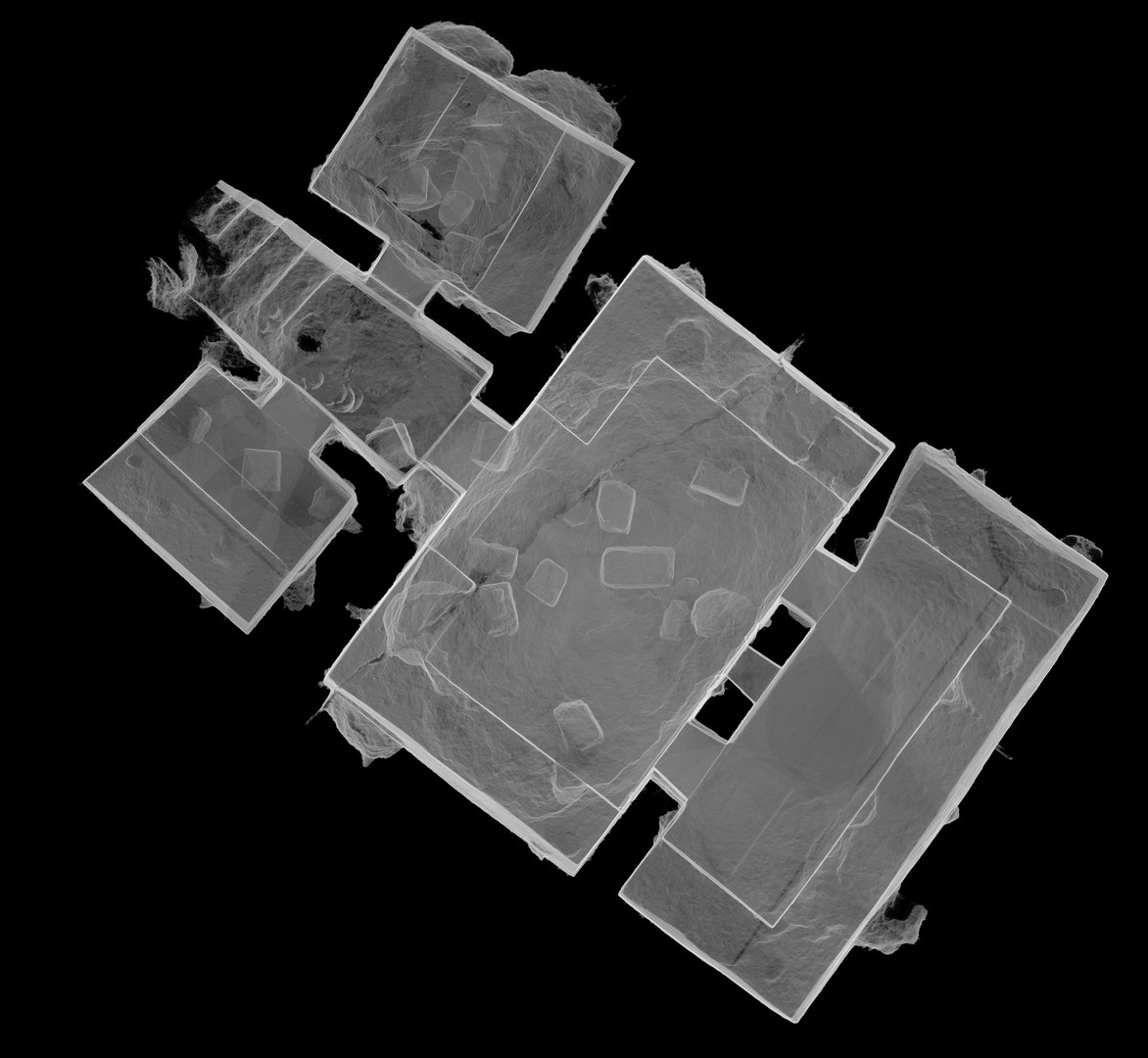

Creating virtual facsimiles of these historical spaces and objects that can later be explored and experienced is a complex process involving many steps. Laser beams are used to scan the spaces to create a three-dimensional model whose dimensions are accurate to a few millimeters. At the same time high-resolution photographs are taken so that the 3D models can be colored correctly.

To enable the resulting models to be explored at the right scale and in high definition using a VR headset, a software framework known as a game engine is used to create the virtual worlds. In this particular case, the Unreal Engine was used, which is the game engine behind such well-known games as Fortnite.

The BCDH team does not just record the spatial layout of the sites, but also digitalizes the archaeological findings from excavations so that they are also available as virtual objects. By including these objects, the project is aiming to take things to the next level. As Matthias Lang explains: “In the virtual world we are able to move and place objects freely within the site. So, for example, we can take objects which have been stored in museums around the world for many years and return them virtually to their original locations. At the same time, we can incorporate a great deal of information in the form of texts, videos or audio files which allow us to experience a completely new form of object-based learning.”

But the goal is not to reconstruct a museum. “What we are not doing is working for months to create a static museum exhibition that will later be dismantled and removed. Our aim is to keep these digital worlds as alive as possible and to continually enrich them by adding information and objects,” explains Lang. This means that all of the data collected has to be archived in a format that will ensure its long-term availability and accessibility, so that these data holdings can be shared with museums or other universities.

Immersion – Diving into a virtual world

One of the key concepts in this field is that of immersion. How can one make experiencing archaeological excavations and ruins as vivid as possible? And how can one integrate personal feelings and impressions into the simulation – or should one even try? According to Lang, questions like “What does a necropolis in Egypt smell like?” or “What would I hear if I was at an excavation site?” are typical of this type of approach. “This is why it is so important that the impact of the virtual world is carefully correlated with the impressions gained at the original site. This means that the person responsible for modeling the virtual world must know the real location being modeled so that his or her own personal, subjective impressions can be incorporated into the model, thus making it as vivid and realistic as possible.”

Digital teaching

The project has a strong didactic component. Questions of interest in this regard are: What form of presentation works well in a simulation? Which elements and methods can be used to communicate key curricular content? “Experience has shown us that the spoken language is particularly well suited to explaining relationships within the model, while written texts are often found to be difficult to read and are often perceived as foreign elements that disrupt the users sense of immersion in the virtual world,” explains Lang.

A prototype is planned for the beginning of 2022 that students will be able to explore wearing VR headsets. “While our teaching objectives and the curriculum have not changed, the methods and tools we use have,” says Lang in summary. Many archaeological institutes still hold collections – some very extensive – of plaster casts of antique sculptures or they have sets of architectural models that still find significant use for teaching purposes. Virtual reality is simply one further step along this path.