Organoids of the human retina

What mechanisms lie behind retinal diseases? To attempt to answer this question, biotechnologist Professor Volker Busskamp and immunologist Professor Elvira Mass are developing so-called retinal organoids in their joint project. These are small pieces of retinal tissue that are made out of stem cells and designed to mimic organs. This provides a good way to study complex mechanisms such as the interaction between cells in a healthy and diseased state, and the findings obtained are crucial for developing suitable treatments. However, the retinal organoids created to date do not have a vascular system or any immune cells such as microglia, the macrophages that can be found in the brain. As organoids like these are similar to embryonic tissue, they are not suitable for mimicking age-related diseases such as age-related macular degeneration.

So the two researchers are now pooling their expertise. Volker Busskamp specializes in investigating retinal degeneration using stem cells, while Elvira Mass is an expert in immunology and studies macrophages in particular, which include microglia. The pair want to generate endothelial and microglial cells from human stem cells in growing retinal organoids, which will result in nutrients and oxygen being supplied to the inner tissues. The researchers are confident that, if their approach works, it will not only inject fresh momentum into creating organoids of the human retina but will also help to develop other organoid models complete with vessels and immune cells.

The Life and Medical Sciences (LIMES) Institute at the University of Bonn and the Ophthalmic Clinic at the University Hospital Bonn are also involved in the project.

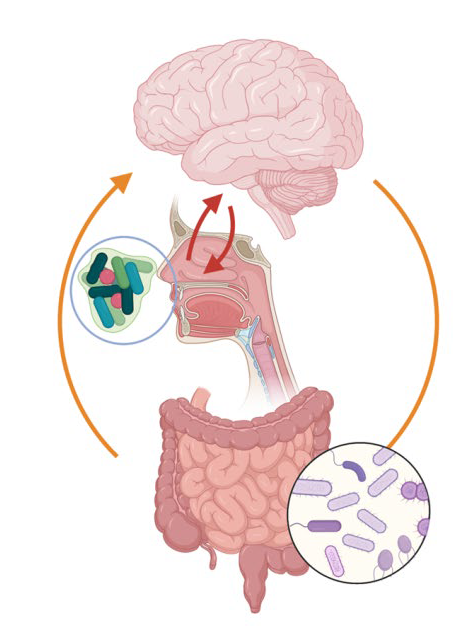

What does the nasal microbiome have to do with Alzheimer’s?

The nasal microbiome meets Alzheimer’s disease: in their joint project, food scientist Professor Marie-Christine Simon, psychiatrist Professor Anja Schneider and neuropsychologist Professor Michael Wagner are investigating the link between the two, which has been little researched to date. As the nose is closely connected to the brain in anatomical terms via the olfactory nerve, the nasal microbiome, i.e. all the bacteria inside the nose, can exert an influence on brain function—in a similar way to the gut microbiome, which is linked to the brain via the gut-brain axis.

There are already indications that this might be the case: for instance, researchers have been able to demonstrate that an impaired sense of smell can be a precursor to symptomatic Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. In the case of Alzheimer’s, the region of the brain that receives direct input from the olfactory bulb is also the first region to detect a change in the “tau protein,” a key sign of the disease. Up until now, however, no tests have ever been carried out on people to see whether molecular changes in the nasal microbiome and associated inflammations contribute to the emergence and progression of Alzheimer’s disease. To establish possible links, the transdisciplinary research team now wants to study the nasal microbiome of Alzheimer’s patients (both early-stage and when the disease is manifest) and of healthy control individuals.

The Institute of Nutritional and Food Science at the University of Bonn and the Clinic for Neurodegenerative Diseases and Geriatric Psychiatry at the University Hospital Bonn are also involved in the project.