The old Film Club

As we approach the University Archive, Dr. Becker stops at an inconspicuous door and opens it—it leads to the underground. Passing through dimly lit corridors, old film posters seem to be hanging on the walls just up ahead. This is the old film club, now defunct. But instead of tattered cinema seats and film canisters there are lines of shelves filling what is now a file room. The walls are painted, depicting movies scenes. “I will be sad indeed if all this perishes in the renovation,” says Becker, “for this space is a monument to bygone days of student culture.”

Students watched movies in Lecture Hall I up until the 1980s, but then the 16mm film projector broke down at the same time as a renovation project kicked off for the two lecture halls that would take ten years. It took until 1996 for the film club to acquire a new projector and restart their activities. In the years in between however, the relatively luxurious Cineplex cinemas had emerged and become popular. Disinclined to watch movies sitting on hard wooden benches, students defected and the film club dissolved. Traces of those days can still be recognized above the basement level too, like the projector chamber in Lecture Hall I, and the old cinema box office opposite the entrance.

Vaulted ceilings above 4.5 kilometers of archived materials

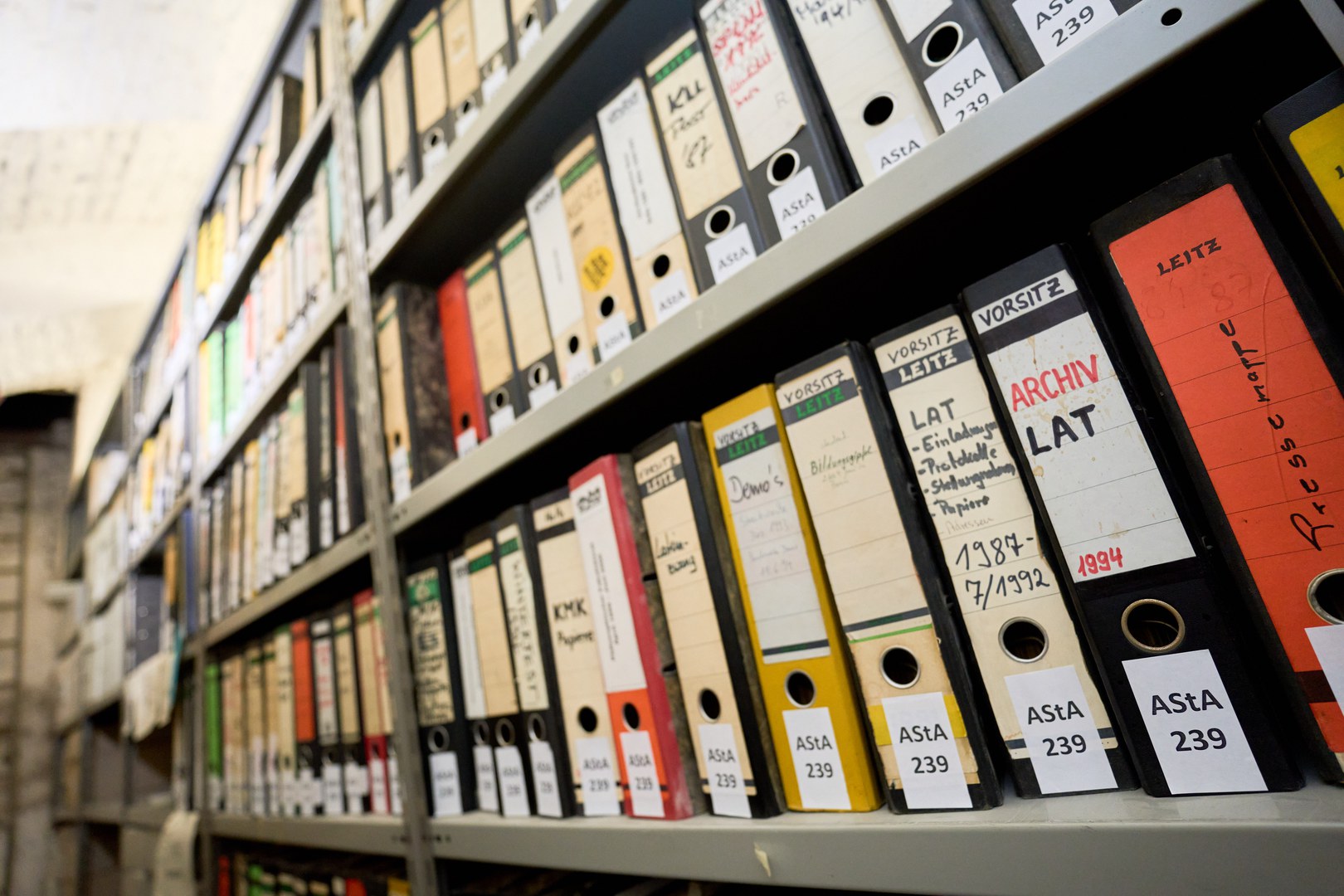

Somewhat like an octopus, the Archive extends through much of the basement level, where over 200 years of University history rest in silence. Matriculation books, colorful General Students’ Committee folders, personnel files, floorplans, photos ... One thousand square meters, 4.5 kilometers of files. HR staff have reason to come down here from time to time, but mostly it’s only Archive staff down there keeping an eye on things like how the dehumidifiers are running, or to process files for preservation in gray archive boxes as perhaps needed in generations to come.

The Archive staff are busy getting things ready to move out and into the basement of the former Deutscher Herold insurance company building, which has a modern compact system that is much better for the files. “Unfortunately however, the guided tours and all the flair of this place ... it will all be going away. So much charm will be lost,” observes Becker, ruefully.

Archivist Becker has been a guardian of the University’s memory center since 1995, concerned as well with the presentation of the institution’s history. “I have always felt connection with the University of Bonn,” he relates, “there’s a special atmosphere here.” The University Main Building has been a fascination for him ever since his student days, thus he views it as one of his major accomplishments having spearheaded the opening of the University Museum in 2013, with dedicated entrance on the Kaiserplatz.

Flood-proof bomb shelter

Dr. Becker leads us into one of the larger spaces of the Archive with vaulted ceilings, originally built in a phase of construction lasting from 1679 until 1715. The ceilings were reinforced in the 1930s or 1940s, for as he relates, “the space was maintained as an air raid shelter accommodating several hundred people.”

In the devastating British air raid of October 18, 1944, University staff found effective shelter there. The Rector had canceled planned ceremonies and the semester opening on the date of the University’s founding in precaution, but administrative staff were at work when the sirens started wailing at 11 am. They fled into the bunker and remained safe, even as the nearby east wing at the Blue Grotto was totally destroyed.

“We are bomb-proof and flood-proof,” says Becker, but climate change is a source of concern for archive staff. The humidity level is rising in the basement area, and water has gotten into the building via the escape routes during heavy rainfall, which has become more frequent. “We were bailing water for two or three days,” Becker recalls. What’s more, Archival materials were damaged even in internal areas of the building as water moved through old, unused pipe systems. It took a while before this damage was even noticed.

The ‘death row’ cell

From the main corridor, you enter an adjoining room on the left, then walk through the compact systems for storing archived material. There stands a green metal door with a sign saying “Death Row”—it opens with a little squeak onto one of the many outer chambers. The room bearing this joke name is a repository for files scheduled to be destroyed. “When it rains, a finger-width of water seeps through these walls, so it’s impossible to store anything here for long in here,” Dr. Becker tells us. It’s rare that anyone ever comes in here, but sometimes they hold popular midnight tours with eerie Halloween-type lighting and storytelling.

Tower defense against the people

Basalt boulders and layers of brick protrude from a nearby wall. Is that a section of the old Bonn city wall? No, says Becker, that wall is located a good 200 meters away: “An old engraving from 1598 suggests that a defense tower used to stand here, long ago.” These colossal ruins were integrated during building of the new Electoral Palace. Instead of being part of the city wall, this tower was built within the palace' periphery, as our Archivist explains, the significance being that its defensive purpose was to direct against the citizenry, rather than protecting against enemies outside.

Pink for women, green for men

In earlier days before women had access to higher education, students used to have bulky study books to write in. This practice changed after the war, index cards in two colors being used instead up until 1968. Men were issued a green card, women a pink one.

Women were first allowed to matriculate at the University of Bonn in the winter semester of 1896, either as ‘visiting student’ or enrolled for a teaching degree. They were allowed to take classes in the humanities, and were disqualified from sitting for exams. Things were generally difficult for women back then. “If a student were to even scuff her feet in protest at something, she could get barred from the classroom. Things were like that in Berlin, but the Rhinelanders were more gallant, offering women a place to sit down,” Becker relates. Then in 1908 women were allowed to matriculate with full-fledged student status, and many threw themselves into the natural sciences, inspired by Marie Curie as a role model.

The graduation student transcripts from that time are interesting, like one issued to a Johann Georg Abels from Neuss, which Becker shows us. In addition to grades you can read written evaluations from professors and comments on student conduct, including whether the students was known to be affiliated with associations that had been banned since 1819, and had demonstrated “moral” comportment. “What constituted ‘immoral’ comportment was seen broadly,” explains Becker, starting with insults.

Then there was Karl Marx, as a famous example, who was put in jail for drunkenness and disturbing the peace. “He had it planned out of course,” Becker reveals, for the prospect of being incarcerated in the cell up on top of Koblenz Gate was not much of a deterrent. Students would often get themselves jail time there on purpose, because the cell door had no lock, and the guard, or “beadle”, had a day job at the University, so while serving time the inmate would go hang out at the Rhine, play cards and go for walks.

The escape tunnels

We are standing in front of a fire protection door, which Dr. Becker notes is new. His key fits, and we proceed into a small chamber. Inside is a ladder extending three meters, amid thick utility lines. “This corridor runs 140 meters from the Palace Chapel to somewhere under the cafeteria, where it stops,” Becker informs us. Its historical use is not known with certainty, and there is no cellar beneath. “It may have been made to balance pressure—but no one really knows for sure.” Lots of building documents were destroyed in the fire of 1777, which went on for several days.

Could this then be the escape tunnel to Poppelsdorf one hears about? Becker believes this conjecture is probably incorrect. “Bonn is a very hilly place. As you move toward the Rhine and Poppelsdorf Palace, the land slopes downward. And between lies the Gumme, the old arm of the Rhine.” So if a tunnel to the palace existed, to use it the Elector would have had wade through groundwater. Furthermore, it would not be very logical having an escape route to Poppelsdorfer Palace, which was unprotected and would be the first place captured by an enemy. “The safer flight route is across the Rhine, but the wings of the original palace structure already extended nearly that far. So you wouldn’t need a special tunnel,” Becker contends.

A crawlspace by the side of the road

A similar corridor exists beneath the stairwell of the auditorium. A ladder at the side of a vault leads up to a wooden door. Behind is a crawlspace with a centimeter-thick layer of dirt; you can see the street through slits and people strolling by.

Finding out what this approximately 20 meter long passage is all about takes one on a deep dive into the history of the Palace. Prince-Elector Archbishop Ferdinand von Wittelsbach added a corner wing onto the original Electoral Residence, which ran parallel to the street “Am Hof” extant today. “The vault here is part of this section Ferdinand had built,” Becker elucidates, parts of which in fact stemmed from an even older public building, as indicated by newer reinforcements implemented. But the crawlspace is located outside the thick walls. So what are its origins?

Ferdinand’s structure was destroyed in the siege of 1689. Joseph Clemens of Bavaria (1671–1723), Archbishop of Cologne and Elector, and his successor Clemens August (1700–1761) built a magnificent four-wing palace complex—which was destroyed by fire in 1777. The modest successor building consisted of two towers and a connecting structure on the side of the Hofgarten. The Palace building proved too small not long after founding of the University in 1818. The University expanded the building in 1926 in a design with four sides and towers, inspired by plans from the Elector era. The Palace was widened by two meters on the street side, and during this work this rammed earth crawlway was created that was likely utilized for utility lines. Dr. Becker explains why tales have come to be told about these secret passages: “Renovation and conversion work has been going on here for 400 years, leaving all kinds of little walled-up passages and chambers whose purpose is no longer apparent. This uncertainty provides a natural impetus for rumor and storytelling.”

Stables and tasting room

A hall-sized area now opens up before us with broad arches—a space whose purpose long remained a mystery. But Becker knows the real story: “This is the only remaining section of the basement of the first residential palace from the 16th century. The arches mark the entrance, and the horse stables were once down here, opening out onto the Etscheidhof.”

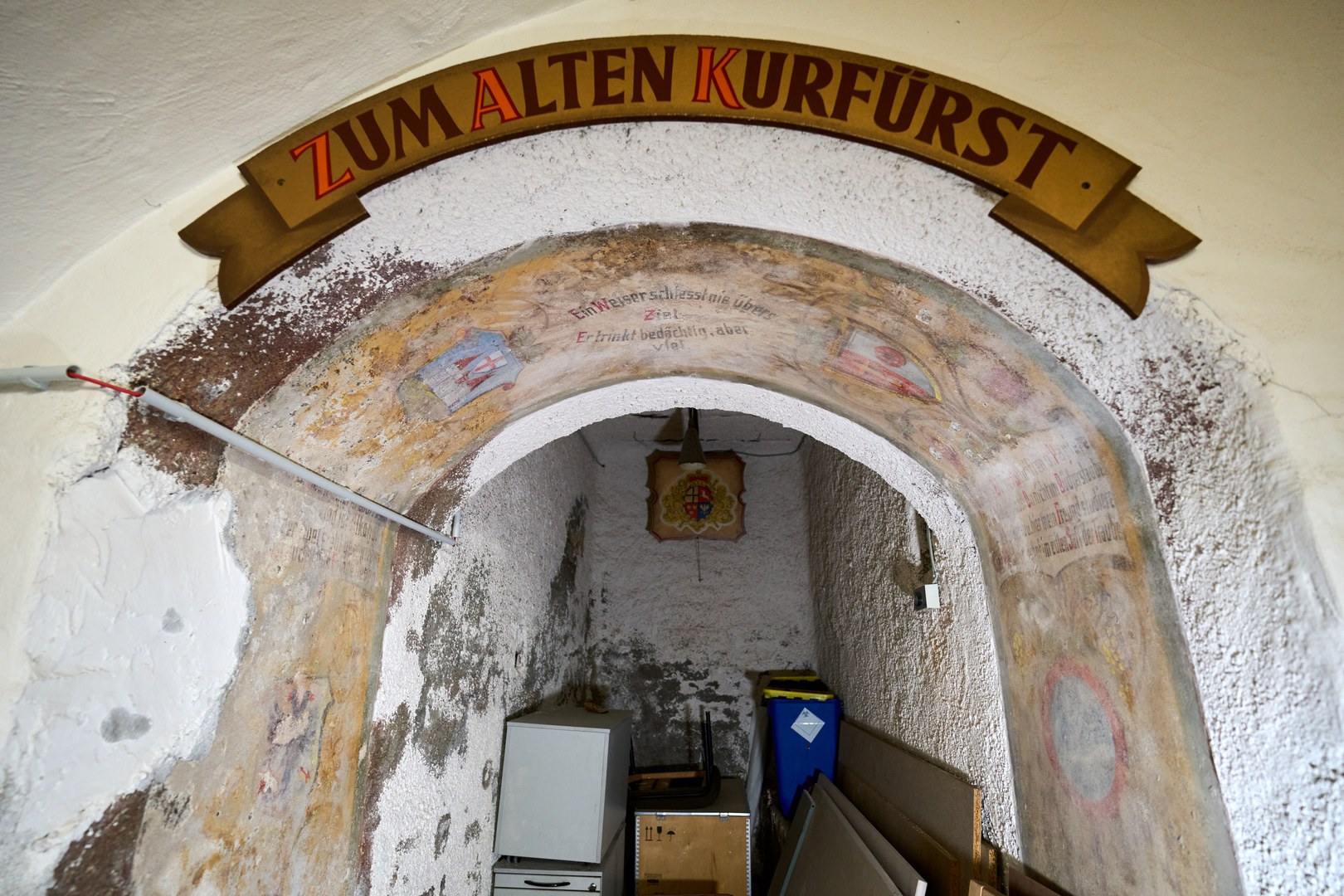

On the way up a staircase to the side a sign emblazoned with the words Zum alten Kurfürst is seen at the top, the back of which bears the coat of arms of the Electoral Brewery. The vault space was rented by the restaurant Weinhaus Streng located in Mauspfad street, and used as a tasting room on into the 1970s. The had their wine cellars in the Palace, whereas today in the old basement stables one finds pallets full of toilet paper in storage.

Cows out to pasture on the Hofgarten and the old bike cellar

Becker is able to dispel another campus myth: Bonn has had an agricultural college since 1847, around which a legend arose that every professor had the right to graze a goat out along the boulevard Poppelsdorfer Allee. The college turned into a faculty of the University in 1934, and the legend evolved along with it, as a goat became a cow, with grazing rights in the Hofgarten. “Completely made up,” Becker says, We were founded in the 19th century, and benefits of that sort were not usually offered at modern universities.” There was, however, a cow in the Hofgarten, one which students presented the Rector with at the summer festival of 1960.

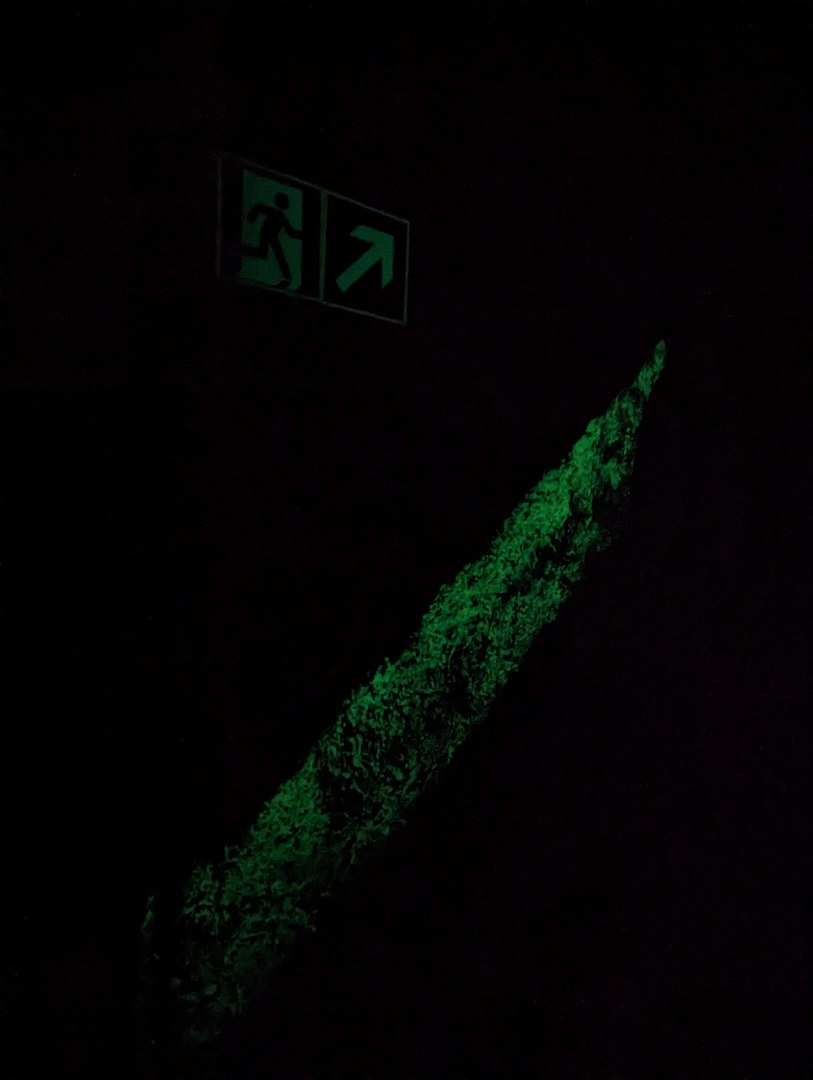

The entrance to the University’s old bike cellar lies a bit off the beaten track. Steep stairs lead down, where a sign informs the visitor of where they are. This was an air raid shelter during the war, as indicated by phosphorescent light strips on the walls. Around the corner lies the old dance hall. They say prominent Journalist Ulrich Wickert once performed ballet here. Despite scant clues of the former parquet flooring, old posters on the wall bear witness to the space’s purpose in bygone days.