Things are busy in intensive care. A short sentence, uttered in passing: “Could you just change Mr. Müller’s Foley in Room 12?” An experienced nurse on this intensive care ward would know straight away what a nursing trainer meant by that: time for a new catheter. Yet it would be something of a riddle not only for a nurse from another country but also for seasoned colleagues based on other wards—and is a problem that Simone Borlinghaus from the IKM Section knows all too well.

“This is a classic case of someone who’s been working there for some time using jargon and not showing enough linguistic awareness,” says the coordinator of the “Perspektive Integration – Sprache im Beruf (PIB)” (“Prospects for Integration—Language at Work”) project, the only one of its kind in Germany.

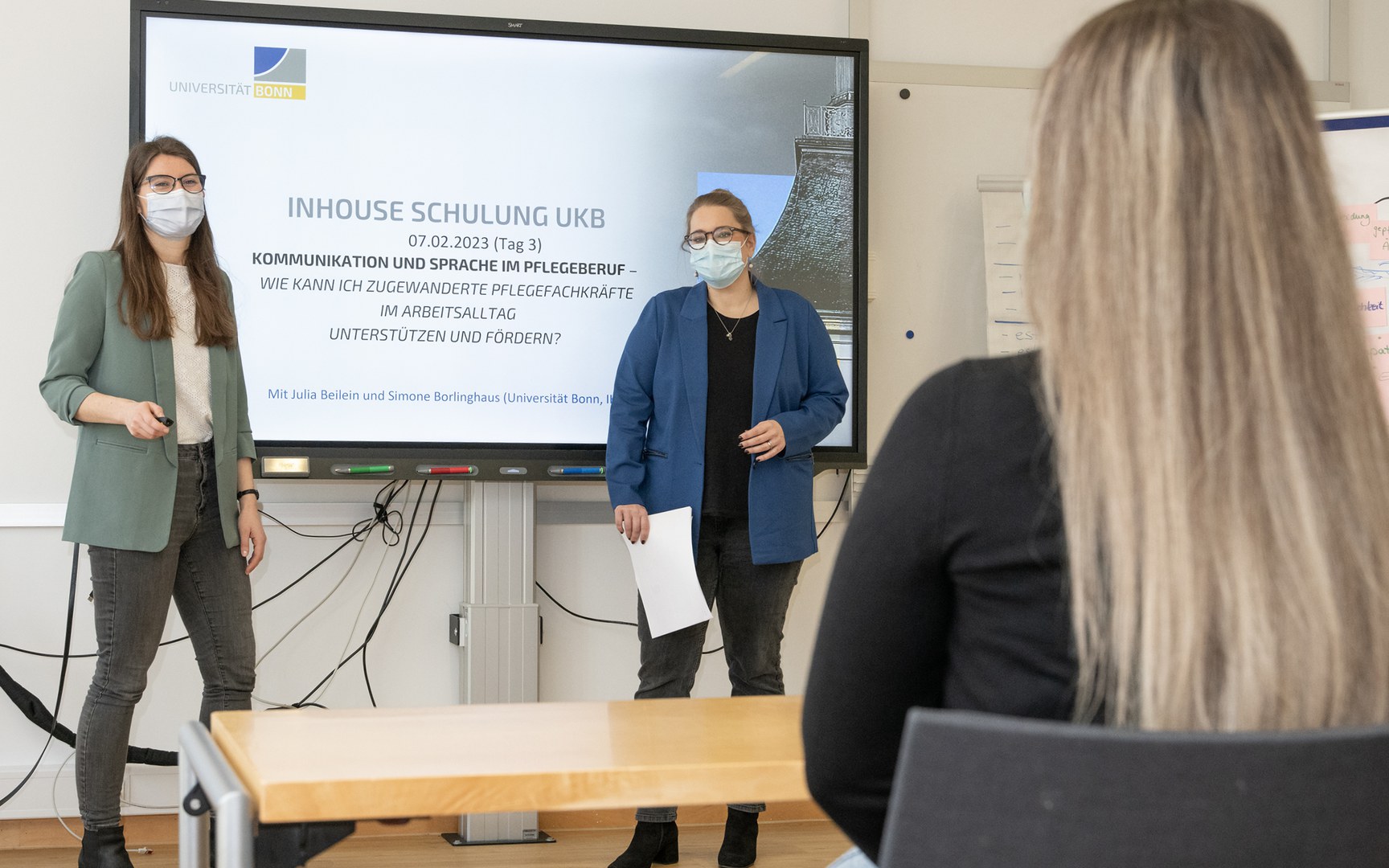

Together with her colleague Julia Beilein, an e-learning expert for the IKM section’s programs for German as a Second Language, she has been giving workplace language training to specialists since 2016 as part of the project. When she saw more and more nurses and healthcare professionals taking part in the continual professional development course, she and Andrea Loibl, a qualified in-company educator and member of the senior nursing team at the University Hospital Bonn, had the idea of organizing a three-day in-house advanced training event for nursing trainers at the hospital. This provided a great opportunity to combine research and practice.

Qualified workers who have only just arrived in Germany face the challenge of not only learning the specific vocabulary of a new working environment in what is for them a foreign country but also of having to get accustomed to an entirely new working culture. “We have several hundred nursing professionals from Asia, Mexico and Eastern Europe with language skills at B1 or B2 level and at least a bachelor’s degree in nursing who stay with us for a long time,” Loibl reports. “Although this gives them a good grounding, the language courses that are offered rarely get them really prepared for their day-to-day work. There’s also room for improvement in terms of the colleagues who are inducting them. With the training, we want to help our nursing trainers to be more aware of the linguistic requirements when they’re inducting their new colleagues and become better communicators.”

Language is the most important tool nursing staff use in their day-to-day work, because they always explain what they are doing as they are doing it. Occasionally, a situation may require them to wear several hats: they must be empathetic and use everyday, easy-to-understand words while also communicating in precise, technical language. “Nursing professionals need to master several linguistic registers,” says Borlinghaus. As Julia Beilein explains, the practical content of the continual professional development course is aligned with the specific place participants work at the University Hospital Bonn: “Before we start, my colleague observes the daily routine on a ward to give her some ideas: What things do people often say? Where are the linguistic stumbling blocks?

Where could we help out from a language perspective?” In the second step, the two researchers teach language training methods to around a dozen nursing trainers and encourage them to reflect on how they themselves use language. “It was a real eye-opener for many people when we were looking for different ways of saying ‘to urinate.’ Of course, not everyone will know colloquial phrases such as ‘peeing’ or ‘going to the little boys’ or little girls’ room.’ Something that a native speaker can generally work out for themselves will be hard for a non-native speaker to understand. Neither is it something that they’re often taught on a language course.” Says Borlinghaus: “We teach our participants about variants of language use such as regiolects, workplace vocabulary and technical jargon, but also about how the various wards often have their own language style that other people won’t understand.” One change that has become established is the introduction of set phrases: “change a Foley” is now “replace a catheter”, for instance.

“This ensures everyone’s on the same page linguistically,” Beilein adds. There have also been improvements to handovers, which can often be hectic: “Materials that we’ve developed and that we’ve adapted to fit individual wards together with the people involved are helping with situations that present a communications challenge such as shift handovers or even phone calls,” she says. “More use is being made of handover sheets, for example. These allow nurses who’ve only just arrived in the country, in particular, to have a written structure for what they’ll need to convey verbally during a handover before they actually have to say it.” Getting the nursing trainers to word their questions in a different way has also proven successful: “Instead of ‘Have you understood?’, they now ask ‘Can you summarize what it is you now need to do?’ or ‘What’s the first thing you need to do now?’” Borlinghaus says.

This is important, she points out, because many of those who have come from abroad are used to different working cultures. “They find it hard to say ‘No, I didn't understand that,’ even if they failed to grasp the tasks at hand on a purely linguistic level,” Borlinghaus explains. Asking targeted follow-up questions helps to identify potential areas of uncertainty in advance, she adds. Loibl states that feedback from the first two series of courses has been very positive and that the content was very well received.

“Many nursing trainers are pleased to get their hands on some important tools and innovative teaching methods for communication and to have the chance to improve their communication skills,” she says. “But they also welcome the opportunity to reflect on their own understanding of their roles and share experiences of integrating and inducting nurses who have come here from another country.” In other words, the benefit is huge: so huge, in fact, that more of these continual professional development courses are being run in 2023.