Read as Visual Story1

On December 9, 1941, Leo Polak was murdered by the Nazis in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. Records from camp staff suggest that he was beaten to death. In February of that year, the Nazis had deported the Dutch free thinker, legal scholar and philosopher from his place of work at the University of Groningen to the camp north of Berlin. Although not a practicing Jew, Polak had Jewish roots. Those of his worldly possessions that he was unable to get to a safe place in time were seized and sold off.

Nine of the books that he owned are now in the USL in Bonn. Tobias Jansen takes them carefully down from the shelf and opens one of them on the first page. “Polak” it says. Whether the nine volumes are in fact looted property is currently being researched. Nevertheless, it is one of many books that perhaps do not belong in Bonn at all but with the heirs of the victims of Nazi crimes. This is the task entrusted to Tobias Jansen as part of the project entitled “Ermittlung von NS-Raubgut in der Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Bonn” (“Identifying items seized by the Nazi regime held at the Bonn University and State Library”), which is being funded by the German Lost Art Foundation.

The USL holds over two million items, and its building on Adenauerallee has three whole floors underground that are home to miles and miles of books on shelves and in rolling stacks. How does one go about finding stolen books in all that? “It’s genuine detective work sometimes,” the historian admits.

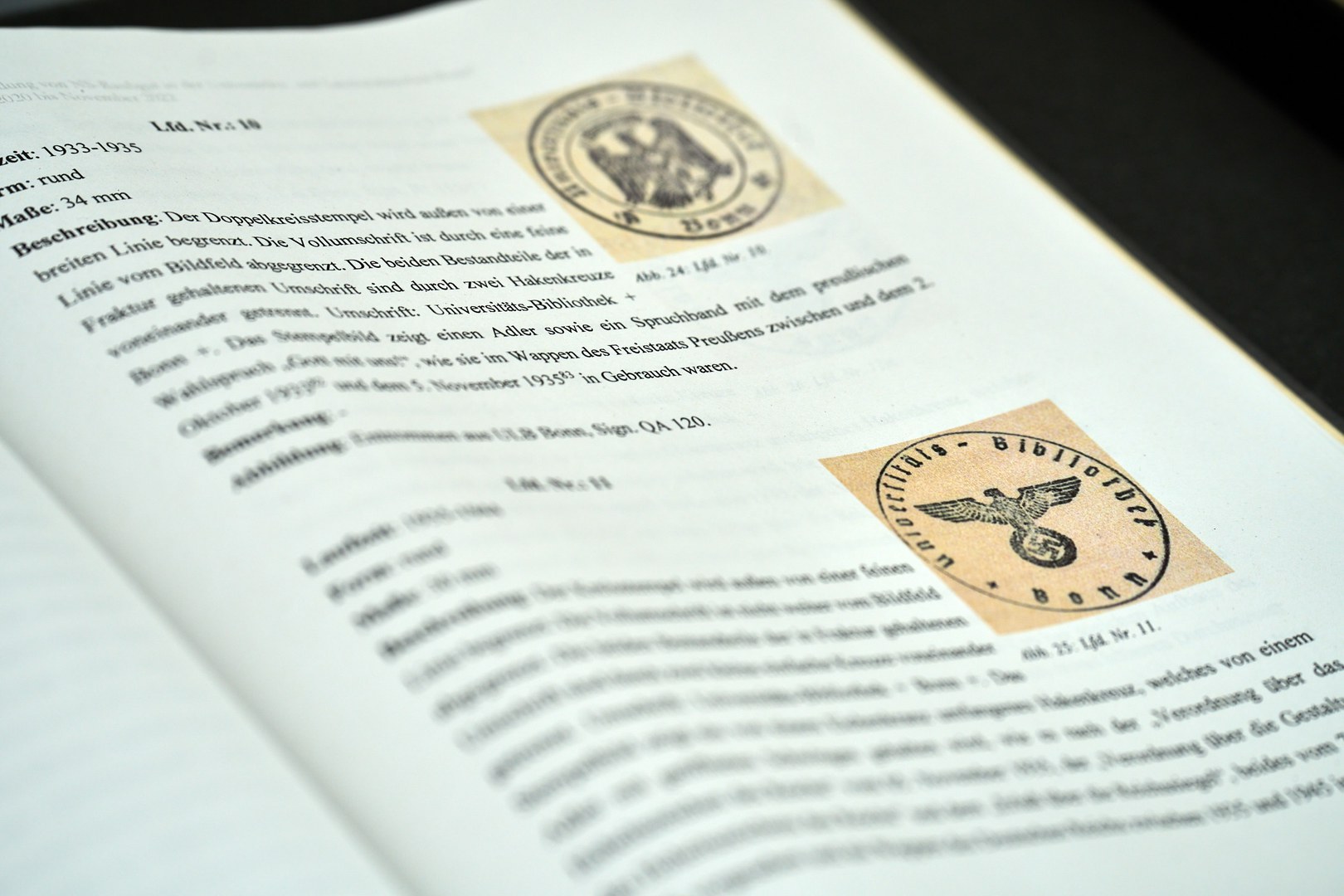

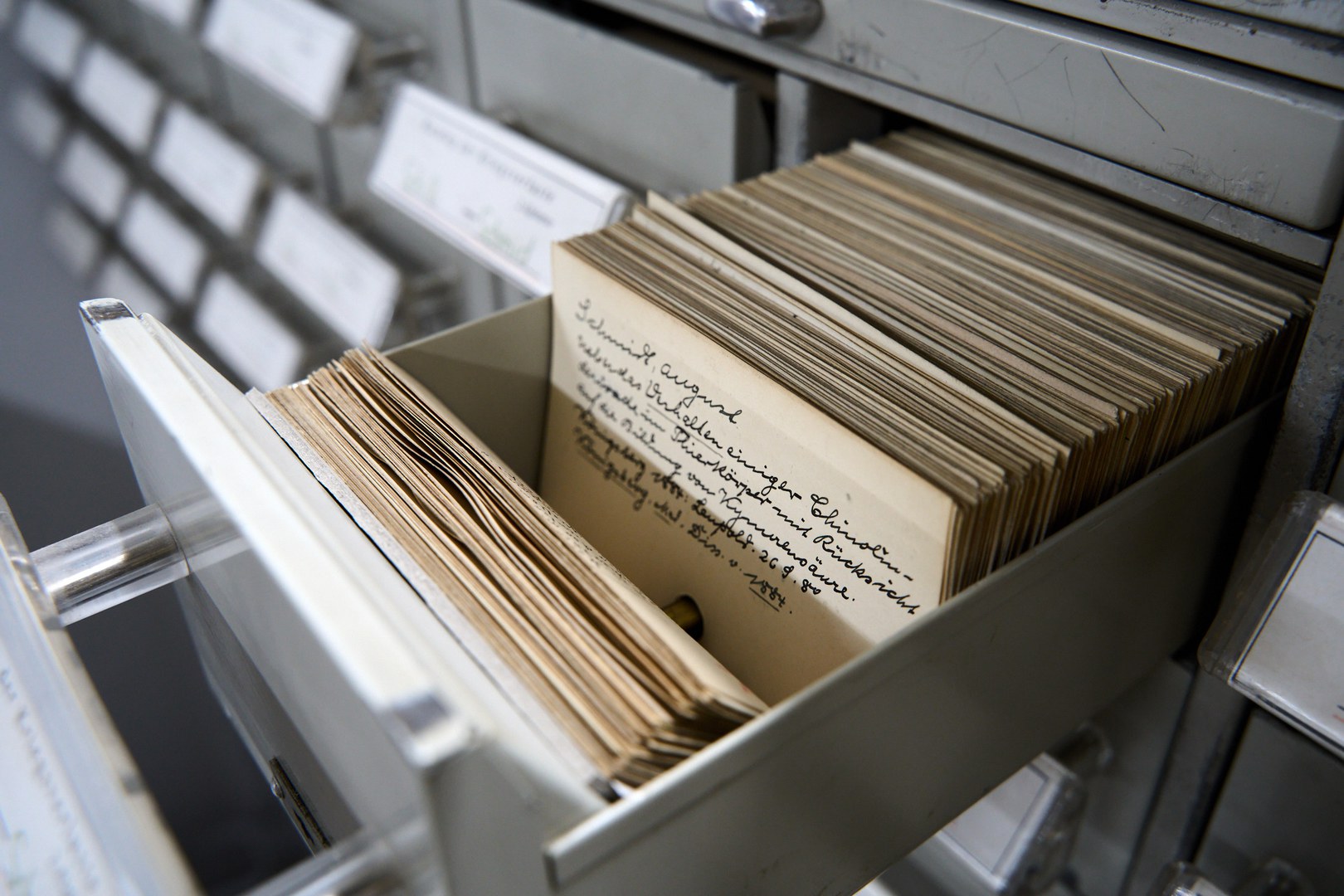

For one thing, however, the holdings can be narrowed down somewhat: obviously, the focus is on items acquired between 1933 and 1950. For another, the books in question would have to have been published before 1945. Every single one of these is flicked through and checked for stamps, initials or other markings that might hold the key to somebody’s story.

“We’re finding out what we have here in the library and getting an idea of the procedures and processes that people followed back then,” Jansen says.

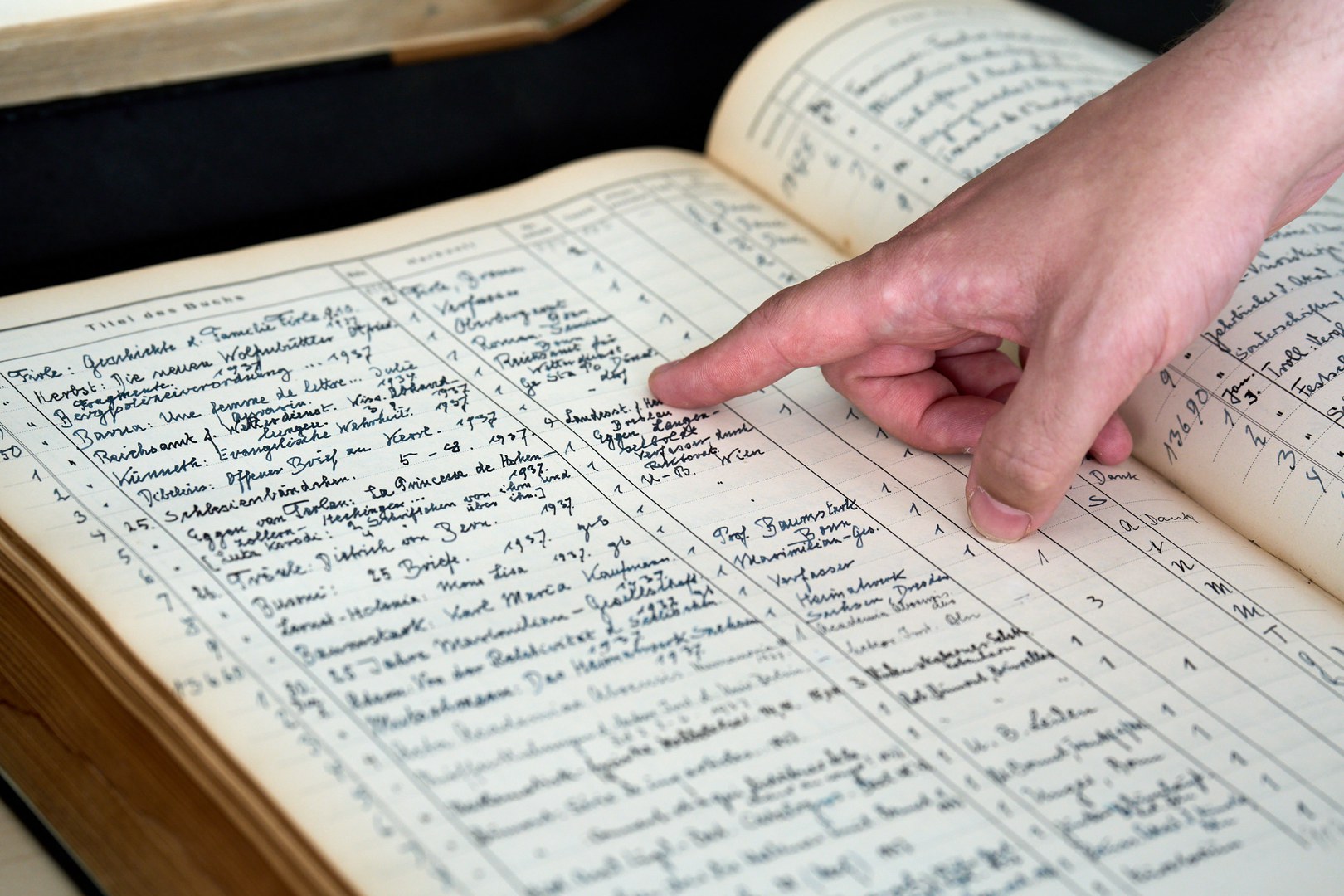

The old accession catalogues are also helping them with their hunt. These lists record over 61,000 acquisitions made between 1933 and 1950, some of which will have included much more than one book. If the accession catalogues contain references to individual books, these are checked against the information from the “Katalog der Kriegsverluste”—the list of items lost during the war. The University library at the time was set on fire by Allied airstrikes in 1944, destroying around 180,000 books. So a book not mentioned in the “Katalog der Kriegsverluste” must be somewhere on the premises. Of these over 61,000 acquisitions, almost 4,000 have now been classified as “suspicious,” while the project team have discovered nearly 600 “strong candidates” that can definitely be assumed to have been seized illegally. And this number is expected to rise even further. Many books will have arrived at Bonn from the training complex that the Nazis called “Ordensburg Vogelsang,” for example. Others, however, will have come from local authorities of the time, such as various town and city halls in the Rhine region, the Gestapo in Düsseldorf or Wuppertal, and antiquarian bookshops—including some major ones—in Germany and abroad.

Jansen pulls a book that only arrived at the USL in 2016 from the blue rolling stack. The work, which actually belongs to a library in Ukraine, was seized from a horticultural college some time before 1944. A soldier in the Wehrmacht had evidently brought it back from the Eastern Front. With Soviet troops massing on the horizon, his wife cut out the library stamp that betrayed the book’s origins. “She was probably afraid that the books would be discovered in her house,” Janssen thinks. If the Russians had found the book, she would have had to come up with a good explanation.

What she did not know, however, was that many books have secret stamps that allow them to be identified in the present day. The horticultural college is now part of a university, and there is a good chance of restoring the book to its rightful home in the long term.

Other high-profile finds include several series of books by the criminal defense lawyer Max Alsberg. Born in Bonn, he studied both here and elsewhere before going on to work as a notary public and criminal defense lawyer in Berlin. As a Jew, Alsberg was persecuted by the Nazis from 1933 onward. Within just a few months, they had destroyed his livelihood and his life’s work, which also included an art and book collection. Desperate and broken, he shot himself in September 1933 in exile in Switzerland.

The books that are rediscovered will be restored to their rightful owners if at all possible, and their origin will be recorded in bonnus, the library’s catalogue, so that the results of the team’s research can be made available to researchers as well as students. An extensive volume of work from the project is being prepared for the coming year. Much of the project’s funding comes from third-party sources, with the rest provided by the USL itself.